Jackson Browne’s relationship with Joni Mitchell

And how it ended up with Not to Blame

Joni and Jackson – a match made in Hell? | Photo: unknown

-

Heaven has no rage like love turned to hatred, nor Hell a fury like a woman scorned

William Congreve

[A] violent and personal attack

David Yaffe, Mitchell biographer, on Not to Blame

Jackson is not violent in any way and the end of relationships are always messy

David Geffen

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Top 🔼

Contents

- Introduction

- The relationship

- Was it violent?

- A rebound relationship?

- Browne’s ’emotional immaturity’

- How it ended

- Phyllis Major

- Mitchell on Major’s suicide

- Not to Blame

- Browne on Mitchell

- Mitchell on Browne

- Conclusion

- An appeal to Joni

- Addendum 1

Old Lady of the Year slur – et al - Addendum 2

Movie news - The end bit

- Reference material

- Comments

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

Introduction

Get the popcorn out, dear Reader

Preface | Preamble

Preface

This post…

-

describes the brief 1972 relationship between Jackson Browne and Joni Mitchell in the context of Mitchell’s 1994 song, Not to Blame;

-

addresses the accusations made in Not to Blame about Browne and Daryl Hannah, and about Browne’s first wife, Phylis Major;

-

concludes Mitchell’s accusations were baseless – and appeals to her to withdraw them.

This began as an annex to my post Jackson Browne & Daryl Hannah about the persisitent rumour that Browne asaulted Hannah. (I conclude he probably didn’t.)

It’s the annex that outgrew its source. It’s still there, but here it’s repurposed and enhanced as a separate post.

This necessarily detailed account of what’s known about Browne and Mitchell’s relationship and its aftermath is an inseparable part of the rumour about Browne and Hannah. Many people condemn Browne solely because they believe Mitchell’s accusatory song Not to Blame.

In forums and comments they say, in effect, referring to Not to Blame, ‘Browne’s an abuser who drove his wife to suicide. Joni Mitchell says so’.

Not to Blame’s believability depends on her relationship with Browne. Mitchell, known for her lyrical integrity, had an affair with Browne and knew him well – so it must be true, right?

But what if it’s not true?

Introduction 🔼

Preamble

70s Joni | Photo: Henry Diltz/Rhino

I love Joni Mitchell’s music. Blue blew my mind, and still does. It’s deeply sad, of course, but can also be deliciously sharp and funny:

- Richard got married to a figure skater

- And he bought her a dishwasher and a coffee percolator

I also love a lot of her other work, earlier and later. She’s complex and unique – a genius.

She’s a superstar and I’m a mere fan. I’m not worthy to lace her size-nine dancing shoes, let alone accuse her of misusing her art and platform out of anger to make a damaging and baseless accusation – but needs must…

Mitchell’s 1972 relationship with Jackson Browne in their Laurel Canyon paradise sounds like a match made in heaven. What could possibly go wrong? Well, quite a lot.

Their relationship and its unhappy ending led eventually to Mitchell releasing her accusatory song Not to Blame (on the award-winning 1994 album Turbulent Indigo).

Mitchell has denied her songs are autobiographical but Not to Blame, released in the wake of the rumour that Browne assaulted Daryl Hannah, is widely understood to be Mitchell’s condemnation of Browne as a wife-beater who drove his first wife, Phyllis Major, to suicide.

In 1976, after bizarrely gatecrashing Major’s funeral, Mitchell made a similar but coded accusation about Major’s suicide in Song For Sharon (on the album Hejira).

18 years later, in Not to Blame, Mitchell not only repeated the current rumour about Browne and Hannah, but – much more damagingly – she again implied Browne was responsible for Major’s suicide.

There was no basis for Mitchell’s accusation. Major had long-term mental health problems and before committing suicide she suffered severe postnatal depression.

Some of Browne’s songs show he and Major had serious relationship problems (see below), but no one apart from Mitchell has made the terrible accusation that Browne drove Major to suicide.

In Not to Blame, Mitchell, clearly directly addressing Browne, said he despised frail women and loved to drive them to suicide:

- [She] had the frailty you despise

- And the looks you love to drive to suicide

This post exposes that accusation as baseless – and probably libellous. Why would Mitchell do that? What went so wrong with her relationship with Browne?

Relationships are normally private but Mitchell’s shocking public accusation against her ex-lover made their relationship public. The scant published information available portrays a love affair that started well but ended badly.

Then came the aftermath: Mitchell’s lasting and overwrought hatred of Browne – a hatred vented some 20 years later in 1994’s Not to Blame.

Mitchell’s abiding hatred for Browne was also publicly aired some 40 years later with bitter comments made in a 2017 biography.

But it all began, dear Reader (or Skimmer), in 1972…

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

The relationship

Such as it was

Joni Mitchell and Jackson Browne began their 1972 relationship whilst touring the US and Europe together.

The tour began in February 1972. Mitchell, 28, was promoting her upcoming fifth album, For the Roses (released in November 1972). Browne, 22, was opening for her and promoting his debut album, Jackson Browne (January 1972).

David Yaffe in Reckless Daughter says after Mitchell’s relationship with James Taylor (see below) had ended, she was…

-

…thrown on the road with Jackson Browne, another brooding singer-songwriter who was even more harmful to Joni’s already fragile emotional state.

[P 167; my bolding]

Mitchell famously said about her thin-skinned Blue period that she felt ‘like a cellophane wrapper on a pack of cigarettes’.

But Yaffe’s suggestion that Browne was more harmful to the fragile Mitchell than Taylor – whilst it matches Mitchell’s vicious character assassination of Browne in Yaffe’s book (see below) – isn’t borne out by accounts of their relationship.

Far from being harmful to Mitchell’s emotional state on the road, Browne apparently lifted it. According to Sheila Weller’s Girls Like Us:

-

When Jackson and Joni dueted on “The Circle Game”, fans saw a chemistry between them. By the end of the tour … “Joni and Jackson were together,” Danny Kortchmar [friend and session guitarist] recalls … “Jackson and I are in love” is how Joni put it to her old flame Roy Blumenfeld [drummer in The Blues Project] when he visited L.A. … “She just fell for him,” says a confidante.

[P 406]

After the tour, back home in LA, they didn’t live together. After a while, their ‘dating’ relationship apparently became turbulent. It ended later the same year.

One possible reason for the turbulence in their relationship was that recently in their neighbourhood of Laurel Canyon, home since the 60s to many LA rock musicians, cocaine had replaced cannabis as the drug of choice.

Moreish cocaine can be addictive, and can cause violence. Did the – possibly cocaine-related – turbulence in their relationship manifest as violence?

There was apparently some violence in both directions (see below), but serious incompatibility seems to have been the main problem. Perhaps they were too different – or too similar.

Weller’s Girls Like Us:

- By the end of 1972…things were not going well between her and Jackson. “It was a high-strung relationship,” says a confidante. Everyone in their crowd was “doing so much cocaine at the time,” and “Joni thrives on conflict, and not many guys can take that”. (“I’m a confronter by nature,” she’s admitted.)…Nonetheless, Joni remained in love with Jackson.

[P 407; my bolding]

Mitchell’s song Car on a Hill (from her 1974 album Court and Spark), said to be about her relationship with Browne, described her growing anxiety and prescient feeling of loss:

- I’ve been sitting up waiting for my sugar to show…

- He said he’d be over three hours ago…

- He makes friends easy, he’s not like me

- I watch for judgement anxiously

- Now where in the city can that boy be?

- He’s a real good talker, I think he’s a friend…

- It always seems so righteous at the start

- When there’s so much laughter, when there’s so much spark

- When there’s so much sweetness in the dark

Around that time, Browne met Phyllis Major, who would become his wife. (See below.) Weller says:

- Jackson’s attention to Phyllis Major felt, to Joni, like “a great loss and a great mind-fuck,” says her confidante. [P 408]

It was Browne who ended his relationship with Mitchell. (See below.) This apparently caused Mitchell to have a nervous breakdown. She spent some time in residential therapy.

However, a scorned Mitchell was also furious. Love turned to hate and rage – and how! Weller:

- Joni remained deeply angry at Jackson for years. Said percussionist Don Alias, who became her serious boyfriend for several years in the late 1970s, “She really had this hatred of Jackson Browne; the whole Jackson Browne thing was really heavy for her.”

[P 410; my bolding]

Sad, but evidently true. Hence, 22 years later, Not to Blame.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

Was it violent?

Not really

There was apparently some violence in the relationship between Jackson Browne and Joni Mitchell, but it clearly wasn’t the habitual kind characteristic of an abusive relationship.

According to David Yaffe’s Reckless Daughter:

-

There was violence of some kind – allegedly in both directions – during Joni’s relationship with Browne. [P 343]

Sheila Weller’s Girls Like Us claims Browne hit Mitchell on one occasion.

According to Weller (as related in a 2008 news report), Mitchell confided to a friend that Browne disrespected her on stage at LA club The Roxy, and they later had an argument, during which he hit her. [P 407]

Weller assured me her source was good. However, Mitchell cast doubt on the credibility of scenes related in Weller’s book when she vetoed a planned movie based on it.

In a 2014 interview, Mitchell said she told the movie’s producer, ‘It’s just a lot of gossip – you don’t have the great scenes’. She also said:

-

‘There’s a lot of nonsense about me in books – assumptions, assumptions, assumptions.’

So there’s questionable hearsay evidence that Browne hit Mitchell on one occasion. On the other hand, Browne claimed Mitchell attacked him during their relationship.

In a 1997 interview about his response to Mitchell’s Not to Blame, he described Mitchell as a violent woman who twice physically attacked him.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

A rebound relationship?

Possibly – but who was on the rebound?

Introduction | Jackson on the rebound? | Joni on the rebound?

A rebound relationship? 🔼

Introduction

(Great chorus – sorry about the YouTube ad)

Did Jackson Browne’s relationship with Joni Mitchell turn sour because it was a rebound relationship?

In David Yaffe’s Reckless Daughter, Mitchell said Browne didn’t return her love. (P 167) (See below). Browne may have referred to that in Fountain of Sorrow (from his 1974 album Late for the Sky).

Browne has denied his songs are autobiographical – something, at least, he shares with Mitchell – but Fountain of Sorrow is widely believed to be about Mitchell. In a 2014 interview, Browne was asked about the meaning of these lines from the song:

- When you see through love’s illusion there lies the danger

- And your perfect lover just looks like a perfect fool

Declining to say who it was about, he nonetheless replied (typically gnomically):

-

‘It’s about the fact that when you fall in love with someone, when you’re broken-hearted, you don’t see them as a person.’

A rebound relationship? 🔼

Jackson on the rebound?

Something fine

Was Browne saying although he loved Mitchell he was still heartbroken from a previous relationship? Was it his continuing focus on a previous lover that so distressed Mitchell?

According to Sheila Weller’s Girls Like Us, Browne was a romantic who said he kept getting his heart crushed. Weller says in 1971 Browne had a brief love affair in London with actor and photographer Salli Sachse, who’d been official photographer for Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. (P 405).

Sachse and Peter Fonda in The Trip, 1967 | Photo: AIP

Weller refers to Sachse as ‘Jackson’s pre-Joni girlfriend‘. [P 410] The ‘you’ in Browne’s Something Fine (from his 1972 debut album,

Jackson Browne) is thought to be Sachse.

In a 2019 interview*, Sachse (an artist living in California) said she left Browne to go to Holland, where she met and fell in love with an artist.

*Sorry – you have to scroll past many pages of rogue code to get to the interview.

Was Browne’s heart crushed again when Sachse left him and fell for another man? Was he on the rebound?

Maybe not. That’s speculation – and it was a short affair, lasting only about 10 days. But it would perhaps explain that strange remark of Browne’s:

-

‘When you fall in love with someone, when you’re broken-hearted, you don’t see them as a person.’

Salli Sachse died in 2025.

A rebound relationship? 🔼

Joni on the rebound?

From James to Jackson

Or was that actually about Mitchell and James Taylor, Mitchell’s pre-Browne lover. Was it Mitchell who was broken-hearted and on the rebound?

Mitchell and Taylor were together from 1970-71. For a while, according to Yaffe, they were very close. (P 127) Then, with Taylor’s growing heroin/opioid addiction and Mitchell entering her thin-skinned Blue period (when, she’s said, she felt ‘like a cellophane wrapper on a pack of cigarettes’), the relationship declined.

James Taylor and Joni Mitchell, 1971 | Photo: Joel Bernstein

According to one account, the relationship was ended by Taylor after Mitchell complained about him flirting with female admirers, and after he’d started seeing Carly Simon.

However, according to Weller, when Taylor and Simon met, Taylor and Mitchell’s relationship had already ended. (P 359) Oddly, neither Yaffe nor Weller describe how it ended, but Weller, writing about Mitchell’s 1972 album For the Roses, said James’ ‘rejection’ got to her. (P 334)

Taylor (in choosing California as his favourite song from Blue) claims Mitchell ended things when she left him in an airport and flew back to California. (Is that what Blue’s This Flight Tonight is ‘about’?)

Who dumped who matters because it’s suggested Mitchell’s lasting anger at Browne stems from him dumping her. But if Taylor also dumped her, how come she’s not angry at him?

Anyhow…was Mitchell broken-hearted when her relationship with Taylor ended? Was Browne – a young, good-looking, cultured singer-songwriter, like Taylor – Mitchell’s rebound substitute? Was Browne referring to Mitchell not seeing him as a person?

Taylor married Carly Simon in November 1972. Did that make the breakup with Browne even worse for Mitchell?

Happy couple: Carly Simon and James Taylor at their wedding, 1972 | Photo: Peter Simon (Carly’s late brother)

However, if Mitchell’s relationship with Browne was a relatively insignificant rebound relationship, why would she remain so intensely bitter towards him 20, 40 years later?

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

Browne’s ’emotional immaturity’

In his own words

There was a 20s age gap between Joni Mitchell and Jackson Browne – she was 28, he was 22. Browne’s relative immaturity probably contributed to the breakdown of their relationship.

Browne has said he was lacking in emotional maturity at that time. He was talking about his song, Ready or Not (on his 1973 album For Everyman).

Ready or Not is about Browne’s first wife Phyllis Major, who he met around the time of his break-up with Mitchell. The song is funny, honest and slightly flippant.

Two verses refer to Major’s apparently unintended pregnancy and to Browne’s uncertainty about settling down:

- Now baby’s feeling funny in the morning

- She says she’s got a lot on her mind

- Nature didn’t give her any warning

- Now she’s going to have to leave her wild ways behind

- She says she doesn’t care if she never spends

- Another night running loose on the town

- She’s gonna be a mother

- Take a look in my eyes and tell me, brother

- If I look like I’m ready

- I told her I had always lived alone

- And I probably always would

- And all I wanted was my freedom

- And she told me that she understood

- But I let her do some of my laundry

- And she slipped a few meals in between

- And the next thing I remember, she was all moved in

- And I was buying her a washing machine

The Songfacts page on Ready or Not (click on the ‘artistfacts’ tab) quotes a Mojo interview* with Browne:

-

‘She [Major] hated that song. She said, “I wasn’t having a baby to get you. And the bullshit about the washing machine is just insulting. So fuck you.” And she was right. I should have said in that song, “Oh shit, I’m about to become a parent and I have no idea how to do this.” But I was not emotionally mature enough.’

[My bolding]

* The interview date isn’t given, and there’s no online archive for Mojo.

In a filmed interview*, a 1970s-looking Browne described Ready or Not as glib, and said – generously – he learned from Mitchell the need to write deeper songs. (And he did – with his next album, the timeless Late for the Sky.)

* The interview was possibly in a TV documentary about Laurel Canyon. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find it again.

Those comments show Browne considered himself relatively immature at that time. With Mitchell, perhaps this was inevitable given the awkward younger-man 20s age gap.

He was, as he sang in Fountain of Sorrow, ‘one or two years’ – six, actually – and (apparently) ‘a couple of changes’ behind her.

Ready or Not portrayed Browne as torn between settling down and freedom. No doubt the immaturity and commitment-aversion shown in the song and acknowledged in his comments on it – along with the age gap – contributed to his apparent incompatibility with Mitchell.

Browne’s casually entitled sexism, as shown in Ready or Not‘s jokey reference to Major doing laundry and cooking meals can’t have helped.

(There was a lot of that around – despite the proclaimed hippy ideals of equality and liberation.)

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

How it ended

Badly

Jackson Browne’s relationship with Joni Mitchell was ended by Browne in 1972 shortly before or after he met his future wife Phyllis Major. Apparently Mitchell was incensed it was Browne who ended it.

She was also apparently distraught. According to Sheila Weller’s 2008 Girls Like Us, a confidante of Mitchell said she attempted suicide by taking pills and she threw herself at a mirror, badly cutting herself. (P 408)

Mitchell has denied this. According to David Yaffe’s 2017 Reckless Daughter, the breakup was ‘less eventful than has been reported elsewhere’ (P 167). Mitchell told Yaffe:

-

‘I read a page in one of those books. It said when Jackson Browne dumped me I attempted suicide and I became a cutter. A cutter! A self-mutilator! I thought, Where do they get this garbage from? I’m not that crazy. I’m crazy, but not that crazy.’ (P 237)

Hmm.

After a period in residential therapy, Mitchell moved into the home of her – and Browne’s – friend and manager, David Geffen.

I asked Geffen about Mitchell’s alleged suicide attempt. He replied to say:

-

‘Everything written about it is either wrong or completely made up … I am not going to talk about Joni’s private life other than to say Jackson is not violent in any way and the end of relationships are always messy.’

(I told Geffen I was asking about Mitchell’s alleged suicide attempt in the course of my investigation into the rumour that Browne assaulted Daryl Hannah. In his reply, Geffen added, ‘Jackson never assaulted Hannah’.)

Yaffe’s Reckless Daughter quotes Larry Klein, Mitchell’s husband from 1982 to 1994, as saying:

-

‘Joni had a great deal of anger towards Jackson … Maybe it stems from the fact that he was the one to end the relationship … I think that’s a pattern in her life. She would do things that would lead to the end of the relationship … and then feel unjustly abandoned.’

[P 167; my bolding]

However, Mitchell’s previous – intense – relationship with James Taylor was also – according to one account – not ended by her – but she seems to have stayed friends with Taylor.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

Phyllis Major

Very sad

Phyllis Major | Photo: source unknown

In late 1972, around the time he ended his relationship with Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne met the woman who was to become his first wife, the actor and model Phyllis Major.

They met in the LA Troubadour club. Apparently Major was being harassed, and Browne intervened. His song Ready or Not (from For Everyman, 1973) included his jaunty account of meeting Major:

- I met her in a crowded barroom

- One of those typical Hollywood scenes

- I was doing my very best Bogart

- But I was having trouble getting into her jeans

- I punched an unemployed actor

- Defending her dignity

- He stood up and knocked me through that barroom door

- And that girl came home with me

Soon after meeting, they began a serious relationship. Their son Ethan was born in 1973. They married in 1975.

Oddly – apparently for no reason – Browne ends Walking Slow (from Late for the Sky, 1974) with these doleful lines:

- I’m feelin’ good today

- But if I die a little farther along

- I’m trusting everyone to carry on

Tragically, it was, of course, Major who died a little farther along and Browne who had to find a way to carry on.

Major had long-term mental health problems and suffered severe postnatal depression. She attempted suicide in 1975, and committed suicide in March 1976 by taking an overdose of barbiturates.

🌷 🌷 🌷

In Not to Blame, Mitchell said Browne drove Major to suicide. (See below.) That terrible accusation is unfounded and uncorroborated – but Browne and Major were apparently having problems.

As a free-spirited and dedicated musician, no doubt Browne was sometimes an absent husband and parent. And Major had a history of mental health issues.

But – as with the relationship between Browne and Mitchell – no one else really knows what went on. I haven’t found any published information about their relationship – apart from in songs.

Disregarding Not to Blame’s uncorroborated accusation, three of Browne’s songs refer to difficulties in his relationship with Major.

- Walking Slow (from the album Late for the Sky, 1974)

- Sleep’s Dark and Silent Gate (from The Pretender, November 1976)

- In the Shape of a Heart (from Lives in the Balance, 1986)

1974’s Walking Slow, despite its breezy tone and its opening lines about being happy and feeling good, refers to marital discord:

- I got a pretty little girl of my own at home

- Sometimes we forget we love each other

- And we fight for no reason

Browne added, presciently:

- I don’t know what I’ll do if she ever leaves me alone

Things were apparently worse than typical marriage tiffs. Sleep’s Dark and Silent Gate, written soon after Major’s suicide, has a verse about their relationship:

- Never shoulda had to try so hard

- To make a love work out, I guess

- I don’t know what love has got to do with happiness

- But the times when we were happy

- Were the times we never tried

It took Browne many years to write a whole song about what went wrong. 1986’s In the Shape of a Heart is very moving – and painfully revealing:

- I guess I never knew what she was talking about

- I guess I never knew what she was living without …

- There was a hole left in the wall from some ancient fight

- About the size of a fist, or something thrown that had missed

- And there were other holes as well, in the house where our nights fell

- Far too many to repair in the time that we were there …

- It was the ruby that she wore, on a stand beside the bed

- In the hour before dawn, when I knew she was gone

- And I held it in my hand for a little while

- And dropped it into the wall, let it go, heard it fall …

- Speak in terms of a life and the living

- Try to find the word for forgiving

Browne’s reference to ‘a hole left in the wall from some ancient fight about the size of a fist, or something thrown that had missed‘ implies him hitting the wall in frustration or her throwing something at him.

The reference to ‘other holes as well in the house where our nights fell, far too many to repair in the time that we were there‘ is clearly metaphorical.

Browne’s not confessing to domestic violence. He’s expanding Walking Slow’s ‘we forget we love each other, and we fight for no reason’ and Sleep’s Dark and Silent Gate’s ‘had to try so hard to make a love work out’ to In the Shape of a Heart’s account of his struggle to cope:

- You keep it up, you try so hard

- To keep a life from coming apart

- And never know

- The shallows and the unseen reefs

- That are there from the start

- In the shape of a heart

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

Mitchell on Major’s suicide

Very bad

Introduction | Song For Sharon | Not to Blame

Mitchell on Major’s suicide 🔼

Introduction

Jackson Browne met his first wife, Phyllis Major, around the time he ended his relationship with Joni Mitchell in 1972. Tragically, Major committed suicide in 1976. (See above.)

In two of her songs, Mitchell has accused Browne of driving Major to suicide.

- The epic Song For Sharon (on the album Hejira) was released in 1976 soon after Major’s suicide. In one of the song’s ten verses, Mitchell implied Browne drove Major to it.

-

The accusatory Not to Blame (on the award-winning album Turbulent Indigo) was released in 1994 in the wake of the rumour that Browne beat Hannah. In addition to boosting that rumour, Mitchell repeated her smear about Major’s suicide more openly – and with spurious detail about Browne and Major’s three-year-old son.

(Not to Blame is analysed in detail in the next section.)

Mitchell was apparently acquainted with Major before Browne met her. In David Yaffe’s Reckless Daughter, she described Major as ‘a sensitive, artistic, beautiful girl, who was passed from guy to guy to guy‘, and said when she learned Major was with Browne, she thought:

-

‘Here comes another one – the worst one of all. The very worst one. And all that shit that she’s gone through to fall into his clutches.’

[P 238 – Yaffe’s italics; my bolding]

(In Yaffe’s book, Mitchell harshly criticised all her exes, but was especially – gratuitously – vicious about Browne. See below.)

Mitchell on Major’s suicide 🔼

Song For Sharon

According to Sheila Weller’s Girls Like Us, Mitchell angered Browne by attending Major’s funeral. Weller says Mitchell saw a parallel with her own suicide attempt and included a coded implication in Song For Sharon that Browne was responsible for Major’s suicide. (P 411)

At the time of writing, Wikipedia‘s description of Song For Sharon – in its entry on the album Hejira – cites Weller’s claim that the song alludes to Major’s suicide. Wikipedia relates Weller’s observation that the song asks if the suicide was a means of ‘punishing someone’.

Mitchell’s beautiful Song For Sharon is a long and rambling autobiographical catch-up (nominally – as it were – addressed to an old friend, Sharon). However, the song’s poetic and sonic beauty conceals an ugly bitterness. Verse five (of ten) is a coded account of Mitchell’s vengeful response to the news of Major’s suicide.

Although Major died from a barbiturate overdose, the verse refers cryptically to a woman who ‘just drowned herself’. It says she was ‘just shaking off futility’ – ie of life with Browne – ‘or punishing somebody’ – ie Browne, presumably for his supposed mistreatment of her:

- A woman I knew just drowned herself

- The well was deep and muddy

- She was just shaking off futility

- Or punishing somebody

- My friends were calling up all day yesterday

- All emotions and abstractions

- It seems we all live so close to that line

- and so far from satisfaction

In Yaffe’s Reckless Daughter there’s no comment from Mitchell about the coded accusation in Song For Sharon. Nevertheless, Yaffe, perhaps referring to unpublished parts of his conversations with Mitchell, describes her emotional compulsion to make that accusation:

-

A woman [Major], who had been married to an ex-lover [Browne], commits suicide. She [Mitchell] feels bad. And she can’t let go of her bitterness toward the man who surely drove her to it, which makes her feel even more sympathy, more anger … She is sad, she is angry, she takes umbrage. She would like to be above settling scores, yet she is compelled to do so. It all came rushing back. Jackson had the nerve to dump her. Then she had such a vivid sense of what was wrong with him, and she could see what he was doing to the women who came after.

[P 236-7; my bolding]

Mitchell on Major’s suicide 🔼

Not to Blame

(Not to Blame is analysed in detail in the next section.)

The bitterness in Song For Sharon was coded and muted. However, 18 years later Mitchell was still bitter – and she let rip.

Mitchell’s song Not to Blame (on the award-winning album Turbulent Indigo), released in 1994 in the wake of the Browne-Hannah rumour, openly and angrily repeated her accusation that Browne drove Major to suicide.

The first two verses of Not to Blame were about Browne and Hannah, but the last verse, cruelly padded with spurious detail about Browne’s son, addressed Major’s suicide:

- I heard your baby say

- When he was only three

- ‘Daddy let’s get some girls

- One for you and one for me’

- His mother had the frailty you despise

- And the looks you love to drive to suicide

- Not one wet eye around

- lonely little grave

- Said ‘He was out of line girl

- You were not to blame’

The spurious detail (‘I heard your baby say …’) referred to Browne and Major’s three-year-old son. Interviewed about Not to Blame in 1997, Browne said:

-

‘It was abusive to employ that image of my son as somebody who treated his mother’s death light-heartedly. I mean, he was a three-year-old baby, you know. This is inexcusable.’

Major took her own life after apparently suffering long-term mental health issues and extreme postnatal depression.

Browne’s songs Walking Slow, Sleep’s Dark and Silent Gate and – especially – In the Shape of a Heart refer to the difficulties they had in their relationship. (See above.)

Those difficulties may have been known to Mitchell – theirs was a small world. However, no one apart from Mitchell (and forum contributors who believe Mitchell’s accusation) has suggested Browne mistreated Major and drove her to suicide.

There’s no corroboration for the nasty accusation Mitchell made in those two songs and – despite Yaffe’s empathic explanation for Song For Sharon‘s coded accusation – no excuse.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

Not to Blame

A sextual analysis of sour revenge

Intro | Verse 1 | Verse 2 | Verse 3 | Outro

Not to Blame 🔼

Intro

Song of hate

In 1994, in the wake of the Jackson Browne-Daryl Hannah rumour – 22 years after her relationship with Browne had ended – Joni Mitchell released her accusatory song Not to Blame (on the award-winning album Turbulent Indigo).

This section offers a detailed analysis of the song, the part it’s played in the rumour about Browne and Hannah, and its reference to the suicide in 1976 of Browne’s first wife, Phyllis Major.

(Mitchell’s twisted take on Major’s suicide in Not to Blame and in the earlier Song For Sharon is also separately addressed above.)

Not to Blame is often invoked in discussion forums and comments as proof Browne’s a wife-beater.

It’s no such thing, but some people seem to think Mitchell’s condemnation of Browne trumps Browne’s protestation of innocence – perhaps because of Mitchell’s stronger reputation and her ‘weaker’ sex.

It doesn’t help, of course, that Browne refuses to explain what happened with Hannah.

Not to Blame offered no proof Browne assaulted anyone or drove them to suicide. Mitchell repeated and embroidered the gossip about Hannah, and she accused Browne of causing Major’s suicide. But the song provided no hint of corroboration or evidence.

For instance, she made no reference to her brief relationship with Browne 20 years previously, despite that being the last time she’d known him.

(Mitchell did talk about their relationship in David Yaffe’s 2017 autobiography, Reckless Daughter. She was highly critical of Browne – see below – but she notably didn’t mention Not to Blame; nor did she repeat her accusations about Hannah’s injuries or Major’s suicide.)

If Not to Blame reveals any truth, it’s not that Browne’s a wife-beater, it’s that Mitchell’s a grudge-holder – and that there’s no rage like love turned to hate.

Not to Blame is beautifully sung over sparse piano chords and sexy bass, with a light, slightly breathless, beguiling purity. Mitchell’s lyrics sound utterly convincing. She doesn’t sound angry or bitter – she sounds like, say, a Norwegian ice-maiden crooning light jazz.

But the song’s dulcet beauty belies its ugly theme: banal vengeance with a poisonous sting.

Not to Blame was released in 1994, when the rumour that Browne beat Hannah was still in the news. The US ‘uncle’ letters about Hannah (see above) had been published that year.

Despite Mitchell’s flimsy pretence that Not to Blame wasn’t about anyone in particular, it was clearly about Browne – and was perfectly timed to twist the knife.

The first verse repeated and embellished the rumour of abuse. The second verse addressed domestic abuse in general (and obscurely accused Browne of ‘perversity’). Then, after that banal bluster, came the madness.

The venomous spite of the third verse was openly aimed at Mitchell’s real target: Browne and Major – albeit cloaked with fake sympathy for Major.

Browne left Mitchell for Major in 1972. Mitchell apparently never got over it.

Major committed suicide in 1976. In the same year, in Hejira’s Song For Sharon, Mitchell implied that Browne caused it.

18 years later, in Not to Blame’s final verse, Mitchell returned to Major’s suicide, accusing Browne of despising women’s frailty and loving to drive them to suicide.

Why did she do that?

In David Yaffe’s autobiography, Reckless Daughter, Yaffe often apparently channels Mitchell in order to explain without quoting. (See, for instance, Yaffe’s explanation for Mitchell’s comment on Major’s suicide in Song For Sharon.)

In that spirit, here’s my channelled explanation for Not to Blame’s third verse:

-

Jackson had left her – genius Joni – for airhead* Phyllis. The shallow bastard! Then Phyllis killed herself. Joni gatecrashed the funeral. She pretended to feel sorry for Phyllis so she could blame Jackson. Her bitterness towards him festered. Now, years later, here was the Daryl Hannah rumour – a chance too good to miss! It had to be his fault! Like Phyllis’s suicide! Like how he left her!! Bastard! Stab! Stab! Stab!

Or something like that. But however you slice it, Not to Blame’s third verse is quite the Psycho scene.

*Major wasn’t an airhead – her reported response to Browne’s Ready or Not shows that – but Mitchell apparently thought she was. In Yaffe’s book, she said Major was ‘passed from guy to guy to guy’ [P 238].

💔

Not to Blame 🔼

Verse 1

Kick!

The first verse got right to it. Jackson Browne had already been damaged by the gossip about Daryl Hannah. Now Joni Mitchell put the boot in by repeating – and embroidering on – the rumour.

The first verse says:

- The media said Browne beat Hannah

- His philanthropy was hypocritical

- She had his fist marks on her face

- His friends said it was her fault and he was not to blame

- The story hit the news from coast to coast

- They said you beat the girl you loved the most

- Your charitable acts seemed out of place

- With the beauty, with your fist marks on her face

- Your buddies all stood by

- They bet their fortunes and their fame

- That she was out of line

- And you were not to blame

In Yaffe’s Reckless Daughter there was no comment from Mitchell on Not to Blame, but Yaffe misleadingly implied the song was Mitchell’s revenge for Browne’s alleged violence against her:

-

There was violence of some kind – allegedly in both directions – during Joni’s relationship with Browne, and this song [Not to Blame] finds her carrying a grudge 20 years later.

[P 343; my bolding]

Allegations of violence in a relationship must be taken seriously, but the alleged occasional two-way violence in their relationship (see above) was clearly not the persistently repeated one-way assault typical of domestic abuse.

In 1994, Mitchell’s 20-year grudge resulted in Not to Blame‘s accusation that Browne was a physical abuser. The grudge, however, can’t have been about physical abuse in their relationship – because the infrequent two-way violence in their relationship clearly didn’t amount to that.

Mitchell’s fiercely derogatory comments on Browne in Yaffe’s book (see below) revealed a long-held grudge (over 40 years by that time) but in the book, she notably – perhaps advisedly – didn’t repeat Not to Blame’s physical abuse smear.

Yaffe was wrong to suggest Mitchell’s grudge was about ‘violence of some kind’ in her relationship with Browne. More accurately, Yaffe went on to describe the song as a ‘violent and personal attack‘. (P 344)

Verse 2

Slice!

The second verse of Not to Blame was less directly accusatory:

- Six hundred thousand doctors

- Are putting on rubber gloves

- And they’re poking at the miseries made of love

- They say they’re learning how to spot

- The battered wives among all the women

- They see bleeding through their lives

- I bleed for your perversity

- These red words that make a stain

- On your white-washed claim

- That she was out of line

- And you were not to blame

However, the second verse seemingly gave a coded explanation for the damning accusation in the third verse – that Jackson Browne despises women’s frailty and habitually makes them suicidal.

In the second verse, Joni Mitchell said, ‘I bleed for your perversity‘. That apparently referred to Browne’s obstinacy in insisting he wasn’t to blame. But was wordsmith Mitchell also implying sexual perversity?

Was Mitchell suggesting Browne was secretly gay and his hiding it was a perversion? Was she saying his secret gay misogyny made him despise women’s frailty and beauty and want to drive them to suicide?

Yaffe’s Reckless Daughter openly suggested Browne was secretly gay. According to Mitchell, Browne’s mother said to her:

-

‘I wondered what form your perversion would take’. (P 167)

Explaining that gnomic comment (a family trait?), Yaffe, apparently channelling Mitchell, said:

-

Joni eventually came to feel she was being given a heads-up. Maybe there was something off about Jackson’s relationships. And he did seem to be more giddy with his male friends than he could ever be with a woman… This guy had issues. [P 167-8; my bolding]

Yaffe told me he got most of the people involved to tell their side of the story, but Browne’s management didn’t respond.

However, it seems likely that whatever Browne’s mother was on about, whatever was ‘off’ in Browne’s relationship with Mitchell, and whatever ‘issues’ he had, he’s not secretly gay.

Perhaps Mitchell was pursuing her vendetta against him by slinging any mud that came to hand.

Whether or not Mitchell subtly loaded all that onto the word ‘perversity’, her accusation that Browne loved to drive beautiful women to suicide couldn’t be justified in any case – it was clearly absurd.

Another accusatory element in the second verse was the phrase ‘battered wives’.

Not to Blame implied Browne beat Hannah, but it didn’t imply he beat Mitchell or any other women. The song’s reference to ‘battered wives’ was ostensibly a general comment about doctors not recognising domestic abuse.

However, ‘battered wives’ might also have been a subtle dig at Browne. A few months before the release of Not to Blame, Daryl Hannah’s uncle, Haskell Wexler, in his much-publicised angry letter to monthly film and music magazine US, said:

-

I was with her in the hospital … The doctor was shocked by the severity and noted Daryl as ‘a badly battered woman’.

[My bolding]

In his reply to Wexler, Browne threatened to go public unless allowed to privately ‘describe Daryl’s actions’. Wexler’s subsequent silence suggests he heard Browne’s explanation and found it plausible – but that wouldn’t have fitted with Mitchell’s bitter preconception.

(Also, Wexler or the doctor may have been exaggerating. According to a contemporaneous People report, although Hannah was seen in New York days after the incident with a bandaged hand and a black eye, 10 days after the incident, the ‘badly battered woman’ was pictured in a paparazzi video ‘smooching’ with JFK Jr in Manhattan.)

Perhaps Mitchell, having seen Wexler’s letter, felt entitled to subliminally enhance her anti-Browne message with the phrase ‘battered wives’.

💔💔💔

Not to Blame 🔼

Verse 3

Stab! Stab! Stab!

In Not to Blame’s third verse, Joni Mitchell finally thrust home the poisoned point: her hatred for Jackson Browne after he left her for Phyllis Major in 1972. In this verse, Mitchell got well and truly Psycho on Browne’s ass.

After Major’s suicide in 1976, Mitchell gatecrashed the funeral. This verse was her twisted account of it, and her even more twisted explanation for Major’s suicide:

- I heard your baby say when he was only three

- ‘Daddy let’s get some girls

- One for you and one for me’

- His mother had the frailty you despise

- And the looks you love to drive to suicide

- Not one wet eye around her lonely little grave

- Said ‘He was out of line girl

- You were not to blame’

In two crazy and vicious lines, she suggested not only that Browne despised his wife’s frailty and drove her to suicide but also that he made a habit of it:

- [She] had the frailty you despise

- And the looks you love to drive to suicide

Major took her own life after apparently suffering long-term mental health issues and extreme postnatal depression.

Browne and Major apparently had relationship problems. (See above.) That may have been known to Mitchell. But no one apart from Mitchell has suggested Browne drove Major – or any other women – to suicide.

Mitchell’s vengeful accusation was a cheesy, melodramatic lie. Such is art made to serve congealed rage.

Mitchell also callously referred to Browne and Major’s three-year-old son:

- I heard your baby say when he was only three

- ‘Daddy let’s get some girls

- One for you and one for me’

If Mitchell, the unwelcome guest at Major’s funeral, heard those words, they were clearly the foolish words of a baby.

Using those words, whether true or invented, to suggest Browne was a womaniser and his three-year-old son was aware of that and was colluding with it at his mother’s funeral was bizarre. It showed the twistedness of her anger.

Interviewed in 1997, Browne said:

-

‘It was abusive to employ that image of my son as somebody who treated his mother’s death light-heartedly. I mean, he was a three-year-old baby, you know.’

Not to Blame 🔼

Outro

Fade to grey

Joni Mitchell should withdraw Not to Blame’s very damaging baseless accusation. It’s not too late for her to put it right. (See my appeal to Mitchell, below.)

In his 1997 interview, Jackson Browne expressed frustration at not being able to talk to Mitchell about Not to Blame.

He said it was inexcusable for her to believe the tabloid gossip, and he was tired of people assuming she was an authority on his life despite not having known him for 20 years.

He said he wrote to Mitchell after hearing the song, but she didn’t reply. He’d tried not to conduct a public defence against Mitchell’s song, but was tired of having to accept her bitter attack.

So Browne had his say – but the song continued to damage him.

In Not to Blame Mitchell used her poetic artistry and her beguiling voice to create the baseless impression of a man who mistreats women, who despises their frailty and loves to drive them to suicide.

The angry and personal tone of the third verse will have convinced some that Browne must be guilty of something terrible. Such is the power of an accusation made by someone of stature.

Mitchell’s reputation – sealed with her unparalleled album, Blue – as the foremost truthful songwriter of her generation, together with her brief but intimate knowledge of Browne, gave Not to Blame an impressive veneer of credibility.

However, behind that cool, authentic exterior, Mitchell was wildly stabbing at Browne like a vengeful goddess* re-enacting the Psycho shower scene.

This song and the unfair damage it’s done to Browne should fade to grey in the limbo reserved for such defamatory fits of passion.

* Thanks to commenter Alan Smith for that apposite epithet.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

Browne on Mitchell

Typically gnomic

Typically tight-lipped, Jackson Browne has said very little about his relationship with Joni Mitchell other than in response to Not to Blame and in contemporaneous lyrics, some of which he’s – kind of – explained.

In a 1997 interview about Not to Blame, Browne described Mitchell as a violent woman who twice physically attacked him during their relationship.

Browne has also spoken about the ‘differences’ alluded to in Fountain of Sorrow (from his 1974 album Late for the Sky), believed to be about Mitchell.

In his spoken introduction to a 2014 videoed performance of Fountain of Sorrow, Browne explained he wrote it for an ex-lover. He’d run into her sometime after they separated, was impressed by her beauty, remembered ‘all the good stuff’, and wrote the song for her. His introduction concluded:

-

‘But as time went on, as years went on, it turned out to be a more generous song than she deserved‘.

The audience’s knowing and sympathetic laughter showed they got Browne’s drily understated reference to Mitchell and her vengeful song, Not to Blame.

Weirdly, however, Fountain of Sorrow isn’t a generous celebration of an ex-lover’s good points at all – it’s a typically deep and soulful meditation on relationships, memory, and loneliness.

- I’m just one or two years and a couple of changes behind you

- In my lessons at love’s pain and heartache school

- Where if you feel too free and you need something to remind you

- There’s this loneliness springing up from your life

- Like a fountain from a pool

Asked in a 2014 interview about that introduction to Fountain of Sorrow, Browne said:

-

‘The things that come to bear in that song are the healing and acceptance of each other’s differences. That’s what I meant by it being more generous than she deserved.’

Hmmm. In the same interview about Fountain of Sorrow Browne was asked about the meaning of these lines:

- When you see through love’s illusion there lies the danger

- And your perfect lover just looks like a perfect fool

He replied, gnomically:

-

‘It’s about the fact that when you fall in love with someone, when you’re broken-hearted, you don’t see them as a person.’ (See above.)

The equally brilliant and moody song Late for the Sky – ‘Looking hard into your eyes, there was nobody I’d ever known‘ – is also thought to be about Mitchell.

Such were Browne’s thoughtful – if not particularly ‘generous’ – reflections on their relationship. Mitchell’s take on it, however, seemed increasingly angry.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

Mitchell on Browne

More heat than light

In 1972, Jackson Browne ended his relationship with Joni Mitchell. Apparently permanently furious ever since, she’s trashed him implicitly in two songs and explicitly in a recent biography.

In 1976, Mitchell’s Song For Sharon, released soon after the suicide of Browne’s first wife Phyllis Major, included a coded implication that Browne caused Major’s suicide.

In 1994, Mitchell’s uncompromisingly vicious Not to Blame, released in the wake of the Browne-Daryl Hannah rumour (22 years after Mitchell’s relationship with Browne had ended), openly implied Browne was a wife-beater who drove his wife to suicide.

More recently, in David Yaffe’s 2017 biography Reckless Daughter, published 45 years after her relationship with Browne, Mitchell – apparently consumed by bitterness like a modern-day Miss Havisham – brutally dismissed Browne as a worthless nonentity.

Yaffe’s book drew on conversations he recorded in 2015 shortly before Mitchell’s aneurysm.

Surprisingly – perhaps advisedly – Yaffe’s book contained no comments by Mitchell about Not to Blame. (Readers had to rely on the author’s flawed explanation.)

However, Mitchell wasn’t holding back in Yaffe’s book. She lashed out at Browne, describing him as ‘a leering narcissist‘, ‘just a nasty bit of business‘ and ‘the very worst one’.

Some of Mitchell’s comments about Browne in Yaffe’s book were merged with those about her previous lover, singer-songwriter James Taylor.

Taylor and Browne seemed to have almost fused in Mitchell’s mind into a single lump of uselessness – but while she excused Taylor as a junkie, she condemned Browne as actively vile.

Mitchell made the ‘leering narcissist’ comment when speaking about her love not being returned:

-

‘I did love, to the best of my ability, and sometimes, for a while it was reciprocated, and sometimes … they were incapable. James numbed on drugs and Jackson Browne was never attracted to me … when [Jackson] spoke about old lovers, he leered. He was a leering narcissist.’ (Yaffe, P 167)

The ‘nasty bit of business’ comment occurred when Mitchell explained how her sadness was caused by having her self-worth undermined:

-

‘I wasn’t mentally ill. I was sad … When someone’s undermining your self-worth, it’s not a healthy situation. Well, it’s not James’s fault, he’s fucked up. And Jackson’s just a nasty bit of business.’ (Yaffe, P 169)

The ‘very worst one’ comment was about Browne meeting Phyllis Major at the time he ended his relationship with Mitchell. She described Major as ‘a sensitive … girl, who was passed from guy to guy to guy’ (see above), and claimed a horrified concern:

-

‘Here comes another one – the worst one of all. The very worst one. And all that shit that she’s gone through to fall into his clutches.’ [Yaffe, P 238 – Yaffe’s italics; my bolding]

There’s more of this from Mitchell in Yaffe’s and Weller’s books. Yaffe told me he was able to get most of the people involved to tell their side of the story but Browne’s management didn’t respond.

That was probably for the best. Browne must have had his faults, but Mitchell seems to have constructed an alternative reality in which fault is one-sided, exaggerated and vilified.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

Conclusion

A woman scorned

In forum discussions and comments, people say Joni Mitchell’s song Not to Blame shows Jackson Browne assaulted Daryl Hannah and drove his wife Phyllis Major to suicide. But they’re wrong.

My inquiry into the Browne-Hannah rumour, and this detailed post about the Browne-Mitchell relationship and its aftermath shows Not to Blame is an unjustified accusation made in anger.

In 1976 in Song For Sharon, released soon after the suicide of Browne’s first wife, Phyllis Major, Mitchell implied Browne drove her to it.

In 1994 in Not to Blame, released in the wake of the Browne-Hannah rumour, Mitchell boosted that rumour; and, this time, openly accused Browne of driving Major to suicide.

💔

Why did Mitchell lash out in Not to Blame with those damaging smears, 20 years after their relationship had ended? What was it about that brief relationship that made her so vengeful?

Was it simply that Browne didn’t sufficiently return her feelings (perhaps because it was a rebound relationship) and – perhaps even worse – that he ended it?

Was Mitchell inconsolably enraged because he dumped her? Possibly, but James Taylor (Mitchell’s pre-Browne lover) also, apparently, dumped her and they’ve stayed friends – whereas in 2015 she described Browne as ‘just a nasty bit of business’.

He’s got a friend – even if he did dump her | Photo: Marcy Gensic (2018) | Thought bubble: Yaffe [P 169]

Also, Browne and Taylor are apparently good friends. As of late 2021, they were planning to tour together. This suggests Taylor doesn’t share his friend Mitchell’s bad opinion of Browne.

Best of friends: Mr Nasty and Mr Fucked-up | Photo: Taylor’s selfie?

If there’s more to it than the indignity of Browne being the one to end it, perhaps it’s the depth of Mitchell’s feelings for Browne – feelings apparently not fully returned – and the depth of her despair when he ended their relationship.

In 2017 in David Yaffe’s Reckless Daughter, Mitchell angrily dismissed Browne as deeply selfish and unpleasant – ‘the very worst one’.

No one else has publicly said such things about Browne. Mitchell’s unsupported criticism, so bitter after over 40 years, raises the possibility that in denigrating him she was hiding a painful truth.

Perhaps Browne wasn’t the despicable nobody she portrayed to Yaffe, but was actually the lost love of her life. To paraphrase the poet, there’s no fury like that of a woman scorned and no rage like love turned to hate.

Mitchell’s previous lover, James Taylor, was handsome enough, but Browne was undeniably a very good-looking young man.

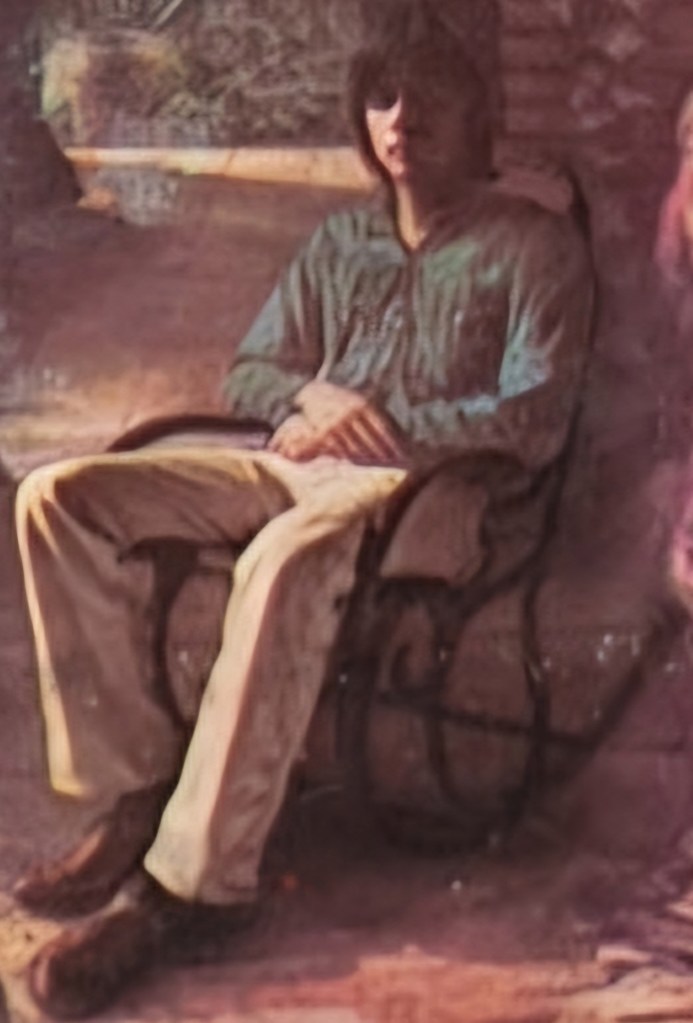

Browne in 1971. Handsome is … | Photo: Henry Diltz

Was Mitchell entranced by Browne’s combination of talent and beauty – and hopelessly in love with him? As she’s said, ‘I’m a fool for love’.

Perhaps closer to the truth than Mitchell’s bitter comments in Yaffe’s book are her poignant – and erotic – lines about the start of their relationship from Car On A Hill:

- It always seems so righteous at the start

- When there’s so much laughter

- When there’s so much spark

- When there’s so much sweetness in the dark

Did Browne inadvertently get through Mitchell’s defences like no one else – and leave her permanently embittered when he ended their relationship?

In his 1997 interview about Not to Blame, Browne said, ‘She and every one of her friends knows – it’s all about carrying a torch’.

💔

Is that the explanation for Mitchell’s lasting bitter anger and its expression in Not to Blame‘s spiteful slur?

We’ll probably never know – Browne has mainly kept quiet about their relationship, and Mitchell’s heated outbursts have shed little light.

Whatever happened and whatever Mitchell’s state of mind, her relationship with Browne gave Not to Blame considerable credibility.

That song’s defamatory message, boosted by Mitchell’s renown as the truthful songwriter and by her more recent expression of lasting hatred in Yaffe’s biography (see above), has continued to damage Browne’s reputation.

Sheila Weller’s 2008 biography Girls Like Us recounts a brief meeting in 2004:

- Mitchell ran into Browne in a grocery store. He told her he couldn’t bear the animosity between them and the two reportedly buried the hatchet. [P 497]

However, Mitchell’s bitter comments on Browne in Yaffe’s biography (made shortly before her 2015 anneurism) showed the hatchet was buried alright – in Browne’s head.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

An appeal to Joni

Put it right and let it go

Joni Mitchell has said she was thin-skinned and exposed when recording Blue in 1971. If she was still vulnerable in 1972, perhaps the relatively immature Jackson Browne got under her thin skin and accidentally did some lasting damage.

In Not to Blame she used her art to hurt him back. Her more recent comments in David Yaffe’s biography, Reckless Daughter, inflamed the wound.

After all this time, perhaps she could forgive him and retract her claws. Some healing would be good. Not to Blame‘s baseless accusation should be withdrawn…

- Its false note resonates dissonantly

- It should be silenced, allowed to fade away

- It’s a bad spell woven with lurid colours

- It should be undone, allowed to fade to grey

- It’s a bad smell. Light a candle, hey?

Apparently, Joni Mitchell doesn’t use the internet, but a friend might show her my impudent but well meant direct appeal:

- Dear Joni

You’ve said some terrible things about Jackson – and many people believe you.

After Phyllis’s suicide, you implied in Song For Sharon it was his fault.

After the Daryl Hannah incident, you accused him in Not to Blame of being a violent man who drove his wife to suicide.

In that song you said to Jackson, about Phyllis’s death:

[She] had the frailty you despise

And the looks you love to drive to suicide

That was baseless and cruel. But a lot of people believe you. In forums and comments, they say, in effect:

He’s a wife-beater and he drove his wife to suicide. Joni Mitchell says so.

In David Yaffe’s biography, you said Jackson was a ‘leering narcissist’, a ‘nasty bit of business’ and the ‘very worst one’.

No one else has said such extreme things about him. Would your discerning friend James Taylor, who presumably knows Jackson pretty well, be his friend if he shared your view of him?

What d’you say, Joni? You and Jackson were lovers for a while – you know what he was like. Was he really that bad?

If not, however embarrassing it might be after all that bombast, you owe him an apology – as a debt of honour.

Before you die would be good. (Flinch not, dear younger Reader. Those of us over 70 may try to deny it – I do – but we know we’re facing death.)

OK, he pissed you off. He seems to have a knack for doing that. Maybe he broke your heart, and you’ve been lashing out ever since. But don’t take this grudge to the grave.

You guardedly conceded to Cameron Crowe in 1979 that ‘Jackson writes fine songs‘. (Faint praise? Like the grocery where you reportedly ran into each other in 2004, a mere purveyor of fine goods?)

Perhaps he’s not as good as you. Perhaps he’s the Monet to your Manet. But he writes beautiful songs. Like this one – about you:

Fountain of sorrow, fountain of light

You’ve known that hollow sound of your own steps in flight

You’ve had to struggle, you’ve had to fight

To keep understanding and compassion in sight

You could be laughing at me, you’ve got the right

But you go on smiling, so clear and so bright

C’mon, Canada – let it go.

🌷

Cat lady in red: Joni and Bootsy, 2020 | Photo: PR

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

Addendum 1

Old Lady of the Year slur – et al

Cheesy crap

- Introduction

- Old Lady of the Year

- Hollywood’s Hot 100

- Jann Wenner’s anti-Mitchell slurs – why?

- Mitchell’s revenge?

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Old Lady of the Year et al 🔼

Introduction

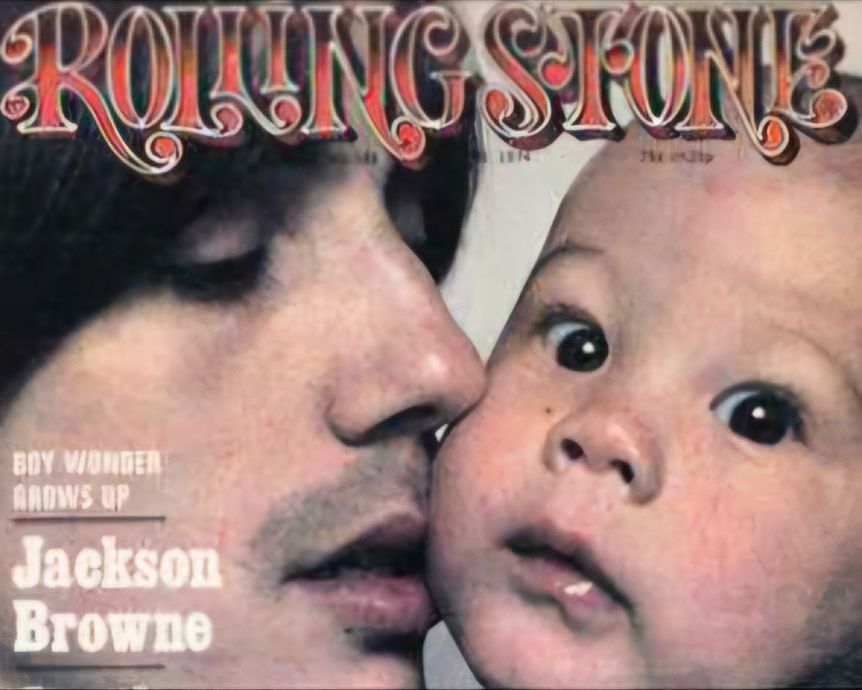

In 1971, Rolling Stone magazine insulted Joni Mitchell by calling her ‘Old Lady of the Year’. A year later, the magazine insulted her again in its ‘Hollywood’s Hot 100’ chart by putting her name in a lipstick kiss.

Those two creepy incidents are detailed here as an addendum partly because they’re so well known, and partly because the second one happened around the time Mitchell got together with Jackson Browne.

They’re not directly relevant to Mitchell’s bitter vendetta against Browne, but they may have worsened her self-confessed downward spiral during that time – when the seeds of bitterness took root.

The two Rolling Stone items are featured on the official Joni Mitchell website, with the Hot 100 introduction and facsimiles of both items.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Old Lady of the Year et al 🔼

Old Lady of the Year

In February 1971, Joni Mitchell was insultingly dubbed ‘Old Lady of the Year’ by Rolling Stone magazine and its famously misogynist co-founder and editor, Jann Wenner.

From Rolling Stone, 4 February 1971 (#75)

Editor: Jann Wenner

In a would-be-humourous 4-page section titled It Happened in 1970: Rolling Stone Annual Awards for Profundity in Arts and Culture, Mitchell got this citation:

-

Old Lady of the Year: Joni Mitchell (for her friendships with David Crosby, Steve Stills, Graham Nash, Neil Young, James Taylor, et al.)

(‘Old lady’ was hippie slang for girlfriend – with, in this case, a snide hint of groupie.)

As it happens, despite the award’s lewd implication, Mitchell’s love life wasn’t promiscuous: it was serial. Crosby and Nash were Mitchell’s exes; and at that time, she was in a relationship with Taylor.

And if a female artist was promiscuous, so what? In the age of free love, sexual equality and the contraceptive pill, it would have been deeply hypocritical to shame her for it.

Stills and Young, also named, were friends of Mitchell. Wenner used the word ‘friendships’ suggestively, leeringly adding the Latin phrase ‘et al’ meaning ‘and others’.

(‘Et al’ is used in academic publications when naming authors. Wenner dropped out of university.)

Perhaps Wenner thought his targeted misogyny was daringly funny. Tastefully adjacent to Mitchell’s award was Wenner’s award for ‘Old Man of the Year’: Charles Manson, for his ‘friendships’ – with his murderous female acolytes. Hilarious, Jann.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Old Lady of the Year et al 🔼

Hollywood’s Hot 100

In February 1972, a year after smearing Joni Mitchell as ‘Old Lady of the Year’, Rolling Stone struck again. Its now-infamous Hollywood’s Hot 100 chart insulted her again – by gratuitously putting her name in a lipstick kiss.

The Hollywood’s Hot 100 chart mapped LA musicians’ musical and ‘romantic’ links. Its introductory text described the LA scene as an ‘incestuous’ society whose members came from several ‘families’.

From Rolling Stone, 3 February 1972

Chart: Jerry Hopkins | Editor: Jann Wenner

Zoomable facsimile

The Hot 100 chart had solid lines for musical links. These links were (and still are) fascinating to music lovers. (The brilliant series of rock family trees by UK journalist, author and historian Pete Frame are similarly fascinating.)

More questionably, the chart had dotted lines for ‘romantic’ links. The dotted lines had heart symbols for existing relationships and broken hearts for previous ones.

The chart linked Mitchell musically to James Taylor, David Crosby, Stephen Stills and Neil Young.

Mitchell was linked ‘romantically’ – by dotted lines with broken hearts – to exes Crosby, Graham Nash and Taylor.

(Mitchell’s 1972 relationship with Jackson Browne hadn’t yet begun – and although Browne was part of that scene and his debut album had just been released, he wasn’t on the Hot 100 chart.)

The Hot 100 chart’s prurient mapping of ‘romantic’ connections was cheesy – but apparently accurate. It could be argued the musical and romantic connections were inseparable parts of the story. As such, the chart was borderline-acceptable.

However, the Hot 100 chart crossed the line by singling Mitchell out for some bizarrely puerile and insulting treatment.

The names of all the other female artists on the chart were printed normally. But Mitchell’s name was printed at an angle inside a large lipstick kiss, with the words ‘Kiss Kiss’ printed three times.

The Hot 100 chart, uncredited in the magazine, was drawn by the late Jerry Hopkins, author and journalist, who’d been Rolling Stone’s LA correspondent in the late 1960s. Hopkins died in 2018.

In Joe Hagans’s 2017 biography of Wenner, Hopkins said he drew the chart as a joke, and it was Wenner who insisted on publishing it. Hopkins said:

-

I was horrified, but not nearly so much as Joni was. I am grateful only that my name was not attached. Joni – if you see this, I’m sorry.

Why didn’t the horrified Hopkins refuse to let his chart be published? Was it owned – perhaps commissioned – by Wenner?

It seems unlikely that Hopkins produced his carefully detailed chart of musical connections as a joke. Perhaps his ‘joke’ comment referred to the chart’s ‘romantic’ connections. Or perhaps he was referring only to Mitchell’s ‘kiss kiss’ lipstick treatment.

But if Hopkins did that as a ‘joke’, then who was the joke meant for? Was it meant to complement his good friend Wenner’s apparent disdain for the LA folk-rock scene and his sniggering ‘Old Lady of the Year’ sense of humour?

Hopkins said he was sorry the chart was published. But was he sorry for the chart’s leeringly crude kiss graphic – which implicitly libelled Mitchell?

Hopkins died in 2018 after a long illness. Perhaps, when he was asked about it for Hagans’s 2017 biography of Wenner, he genuinely regretted that nasty ‘joke’.

In any case, by printing Hopkins‘ offensive Hollywood’s Hot 100 chart in Rolling Stone, Wenner was attacking Mitchell again. But why?

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Old Lady of the Year et al 🔼

Jann Wenner’s anti-Mitchell slurs – why?

Why did Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner insult Joni Mitchell by calling her Old Lady of the Year and printing the Hollywood’s Hot 100 chart with her name in a kiss graphic?

Was it gay misogyny? Although Wenner was married at that time to Rolling Stone co-funder Jane Wenner and was supposedly bisexual, he eventually emerged as gay. Male gay misogyny is a well-kept secret (masked, for instance, by the phenomenon of gay men tolerating straight women claiming close friendship).

Beauty and the Beast: the Wenners, 1968 | Baron Wolman

But those smears – and other later ones, such as saying ‘The Hissing of Summer Lawns’ was the worst album title of the year in 1975 – showed something more focussed than generic gay misogyny.

They showed Wenner’s obsessive personal animosity towards Mitchell (albeit unconvincingly presented as edgy humour).

San Francisco-based Wenner apparently scorned the LA folk-rock scene. (Rolling Stone slammed albums by CSNY, Neil Young and David Crosby.) But something beyond that must have irrationally wound him up.

As the necessarily forceful owner and editor of an internationally successful magazine, perhaps Wenner became autocratic and delusional – and felt entitled to indulge what was apparently his whimsical dislike of Mitchell.

-

Wenner’s future cultural rehab group session: ‘Hi – I’m Jann. I’m an delusional autocrat with an irrational dislike of Joni Mitchell.’

(Mitchell’s: ‘Hi – I’m Joni. I’m holding on to my bitterness and my irrational hatred of Jackson Browne.’)

Whatever its cause, Wenner’s anti-Mitchell campaign showed he had no respect for her widely acknowledged artistry.

That disrespect was life-long. The crass remarks Wenner made about Mitchell some 50 years later helped get him thrown off the board of his beloved Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. (See below.)

Back then, understandably offended by Wenner’s smears, Mitchell boycotted Rolling Stone for many years. Supposedly, she later threw tequila at Wenner during an awards ceremony and was then apparently blacklisted by the magazine – as described in her song Lead Balloon (on Taming the Tiger, 1998).

In 1979, because of her friendship with Rolling Stone writer Cameron Crowe, Mitchell broke her boycott and gave the magazine an interview. She dismissed Rolling Stone’s obsessive interest in her relationships as ‘ludicrous’.

Rolling Stone’s mistreatment of Mitchell continued, but eventually the tide turned. In 2017 Wenner sold his stake in Rolling Stone; and in 2023, the magazine celebrated Mitchell’s overdue ‘Jonissance’ recognition; and belatedly repented its misogynist past.

Also in 2023, Wenner got his overdue comeuppance. Promoting his book of interviews (with exclusively white, male musicians), he vented his disrespect for Mitchell and his disdain for black musicians.

Those remarks led to Wenner’s removal from the board of directors of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame – which he’d co-founded.

Wenner’s editorial animosity was an obstruction on Mitchell’s long and winding road to superstardom. But in the end, she won her righteous feud with Wenner. Hoo fucking rah!

(Now she should end her pointless feud with Browne.)

I’ve asked Jann Wenner for his comments.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Old Lady of the Year et al 🔼

Mitchell’s revenge?

In March 2024, at an award tribute concert for Elton John and Bernie Taupin, Joni Mitchell sang a jazzy, swing version of I’m Still Standing – with her own lyrics.

The song wasn’t, as might be expected, about Mitchell’s ongoing recovery from her 2015 aneurysm. It was apparently her revenge for mistreatment by former Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner – and her celebration of his downfall.

In September 2023, Wenner, the man behind Rolling Stone’s damaging 1970s anti-Mitchell smear campaign, was sacked from the board of directors of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (which he’d co-founded) after he made derogatory remarks about black musicians – and about Mitchell.

For her performance of I’m Still Standing, Mitchell – apparently with the permission of John and Taupin – rewrote the song’s three verses.

Taupin’s lyrics express bitterness about the ending of a relationship. Mitchell’s lyrics – perhaps not her best work – were thematically similar to Taupin’s. They were equally bitter – and aimed at someone who’d wronged her:

- You’ll never know what love is like

- You’re too self-centred and you’re too uptight

- You’re cold and distant and you don’t care

- I’ve seen the ugly side you hide behind that mask you wear

- You’re not happy ’til you make me cry

- That’s not gonna happen – look, my eyes are dry

- And my heart’s not broken and my path is clear

- And you were just a bumpy little detour, Dear

- [Chorus]

- You think you won, you think I lost

- You’d get the sunshine and I’d get the frost

- My life gets better for me every day

- And I’m still standing while you just fade away

- [Chorus]

[Bold: Taupin]

It might be thought Mitchell’s triumphal put-down was about Jackson Browne – keeping the hate warm after 50 years (and ignoring – or, to be fair, probably completely unaware of – this post’s appeal to her to let it go).

But whatever Mitchell thought of Browne, he clearly wasn’t just fading away. Like Mitchell, he was still standing. So it probably wasn’t about him.

The song could have been about the downfall of anyone who’d crossed Mitchell, but the timing of her exultant performance, just six months after her nemesis Wenner was humiliatingly sacked from the board of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, makes him the likely target.

Also, the ‘bumpy little detour’ from Mitchell’s ‘path’ matched this post’s description of Wenner’s campaign as an obstruction in Mitchell’s road to superstardom.

Mitchell can certainly hold a grudge.

Mitchell, who resumed public performances in 2021, was (still) standing on this occasion – with a stick – and was on good form.

The swing arrangement was very catchy, and (apart from some mistiming in the final chorus) Mitchell sang well. In spite of the caustic lyrics, she didn’t sound bitter – she sounded amused!

Mitchell’s eyes were shielded by tinted glasses, but she had a mischievous glint; and she was laughing and smiling. It was good to see.

Not bad for a post-aneurysm 80-year-old. She’s now truly Old Lady of the Year. Take that, Jann!

Smiling assassin, March 2024 | Taylor Hill/WireImage

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

Addendum 2

Movie News 🎬

Friendship and film

Still friends: Crowe and Mitchell, November 2022

Photo: Bruce Glikas/Getty Images

There’s going to be a biopic about Joni Mitchell – but will her feud with Jackson Browne be included?

In 1979, Mitchell broke her anti-Jann Wenner boycott of Rolling Stone by giving an interview to Cameron Crowe. (See above.) After the interview, Mitchell and Crowe became friends.

Crowe became a filmmaker, writing and directing films such as award-winners Almost Famous and Jerry Maguire (and controversial flop Aloha).

In 2023 Mitchell and Crowe, still good friends, were reported to be planning a biopic film about Mitchell.

That was good news – but what about Browne? Would the film defame him, as Mitchell has? Or would it ignore her brief relationship with Browne and its 45-year aftermath?

With Mitchell apparently having an editorial say, the film seemed unlikely to tell the truth about her and Browne.

To complicate things, Crowe was friends with Browne. There was Crowe’s friendly 1974 Rolling Stone cover interview with Browne; in 1982 Browne co-wrote Somebody’s Baby for Crowe’s screenwriting debut, Fast Times at Ridgemont High; and in 2016 Browne guested on Crowe’s flop TV drama Roadies.

So Crowe might understandably prefer to airbrush his friend Browne out of the Mitchell picture. (Like he airbrushed Mitchell out of his 1974 interview with Browne.)

I’ve asked Crowe for his comments on this.

Also…

How about another film from Crowe – about Browne? (With Mitchell airbrushed out, presumably.)

And…ahem…if Crowe or anyone else wants to make a film based on this post – as I write, it’s had over 70,000 views – I’m open to offers. It’s registered with the Writers Guild of America. In my (deluded) imagination, I see it as a heightened docudrama.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

The end bit

Unhappy ending

Jackson Browne’s relationships with Joni Mitchell, Phylis Major and Daryl Hannah suggest not that he was an abusive man who liked to drive women to suicide, but rather that he was attracted to troubled women. It happens. Happily, he’s now apparently in a comparitively untroubled relationship.

Joni Mitchell, meanwhile, continues unrepentantly to be… Joni Mitchell. She should repent – if only for her own sake – of her pointless grudge against Browne. But she seems bitterly determined to take it to the grave, like a Norwegian snow-queen version of Miss Havisham.

Dear Reader, this sorry tale is told. Browne and Mitchell, briefly together in beautiful youth, then two middle-aged gods at war, are now ageing artists facing the dying of the light.

This post has sought to counter Mitchells’s libellous anti-Browne campaign. But perhaps in the long run it signifies nothing other then a sad story of love turned to hate. I wish the best to both of them.

Jackson Browne & Joni Mitchell

Contents 🔼

Reference material

Look it up

Books | Wrong! | The unhelpful Rolling Stone interview and the missing book | Official website

Reference material 🔼

Books

Same 1968 photo of Joni on both books | Photo of Mitchell: Jack Robinson/Hulton Archives/Getty Images

This post refers to and quotes from two biographies which cover Jackson Browne and Joni Mitchell’s relationship:

-

Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon and the Journey of a Generation (2008) by best-selling author Sheila Weller

Page numbers from Washington Square Press paperback, 2009

- Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell (2017) by award-winning music writer David Yaffe

Page numbers from Sarah Crichton Books paperback, 2018

-

(There’s an excellent review of Yaffe’s book in Goodreads.)

Weller interviewed confidantes of her three subjects. Yaffe drew mainly on his conversations with Mitchell, recorded in 2015 shortly before her aneurysm.

Reference material 🔼

Wrong!

The two biographies both get one thing wrong when writing about Mitchell’s Not to Blame. They both wrongly say Daryl Hannah accused Browne of assaulting her.

Weller (P 411):

-

Browne’s longtime girlfriend, actress Daryl Hannah, accused him of beating her up

Yaffe (P 343):

-

Hannah claimed that Browne beat her badly enough to put her in a hospital

That’s careless – Hannah made no such explicit accusation. The only public statement made was a carefully worded press release issued on the day of the incident:

- ‘Daryl Hannah received serious injuries incurred during a domestic dispute with Browne for which she sought medical treatment.’

That clever wording implies Browne assaulted her but doesn’t actually say so.

(Why not? I conclude she probably got those injuries when Browne defended himself against her autistic rage attack.)

Reference material 🔼

The unhelpful Rolling Stone interview and the missing book