In which I make a fool of myself with two (or three) quite famous people, discover Laurel and Hardy in the UK’s Lake District, berate touchy creatives who complain about fame, and match UK TV characters Beverly from Abigail’s Party and Alan Partridge.

Updated 2022

🤡

If you see a famous person in public, you recognise them, but you don’t know them. You might admire them for whatever they’ve done that made them famous. Should you speak to them, or should you pretend not to notice them out of respect for their privacy? The thing is, you do know them, in a way. It’s an etiquette conundrum for the reticent British.

In recent years, I’ve had two encounters with celebrities. Neither went well.

Encounter 1

A familiar face

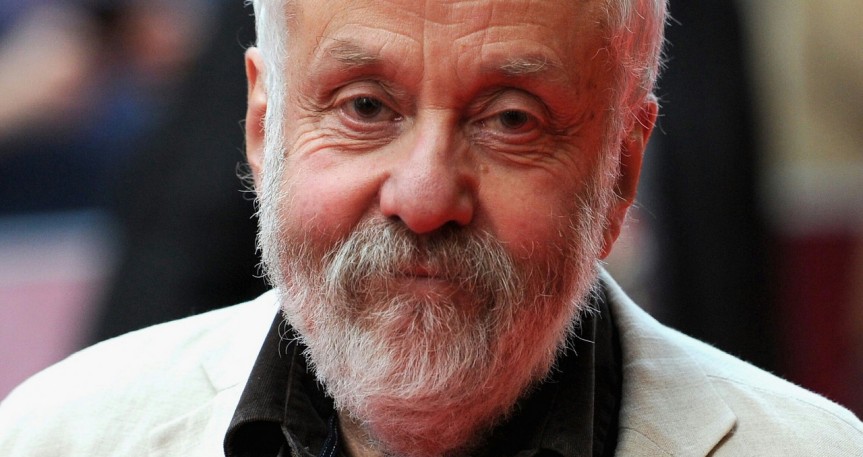

On the first occasion, I saw maverick UK film director Mike Leigh on a street in London’s West End. He was walking towards me and my wife on a crowded pavement. I recognised his distinctive face, but I didn’t realise at the time who he was.

I thought he was someone I knew in real life, so I started to give a facial ‘hello!’ expression, and he – generously (or perhaps instinctively), given that he obviously didn’t know me at all – started to respond with a similar expression.

At that point, I suddenly realised that he was actually a famous person who I didn’t personally know; and that although I recognised him, I didn’t know who he was. We were getting closer. I changed my focus to somewhere over his shoulder, neutralised my expression and walked past him. Awkward.

Encounter 2

Knowing me, not knowing you

On the second occasion, I managed to rachet up the awkwardness. UK TV comic and film actor Steve Coogan and US film actor John C Reilly came into the small country pub near Broughton-in-Furness in Cumbria (aka the UK’s fabulous Lake District), where our party of five were having a meal.

It was a small room with two or three tables. Coogan and Reilly took off their country-style jackets and peaked caps, and sat at another table. They didn’t acknowledge us. I got the impression that perhaps they’d hoped to have the room to themselves.

We recognised them (although I had do some googling afterwards to get Reilly’s name), but we discreetly ignored them while we – and they – were eating, drinking and talking.

It was like a surreal version of Coogan and Rob Brydon‘s brilliant TV spoof restaurant tour of northern England, The Trip, but with Reilly instead of Brydon, and with us (accidentally) hearing only snatches of their conversation.

When we left I decided – emboldened by a couple of pints – to say something to them. Something amusing would be good, I thought. OK, actor-celebs want to be left alone when dining incognito. But deep down, don’t they want to be recognised? Loved, even? I was going to give them some love.

After the rest of our party had filed out, I stopped at the end of Coogan and Reilly’s table. They were deep in conversation. ‘Excuse me’, I said, ‘Sorry to interrupt you.’ They stopped talking and turned to look at me. They both looked wary.

I was going to ask Coogan, ‘Didn’t you used to be Steve Coogan?’ I thought that’d be an amusingly pseudo-stupid cliché. He’d get the joke, we’d have a laugh, and I’d go on my way. What I actually said to Coogan was, ‘Didn’t you used to be on TV?’

I don’t know why I said the wrong thing. I admire Coogan’s work, but I wasn’t particularly starstruck, so it wasn’t that. It was probably a combination of my sudden proximity to the intoxicating world of show business, my audacity tripping me up, and the beer. (And the large gin and tonic before that. Don’t worry – we had a designated driver.)

Anyway, what I actually said wasn’t amusingly pseudo-stupid – it was just stupid. I couldn’t correct myself – that would have made it worse. I could only let it lie. It lay heavily, like a fart in a lift.

Coogan and Reilly both looked – understandably – taken aback. They looked at each other. They shifted in their seats. Coogan said, ‘Er…’ He looked cornered, as if he was taking my question seriously but realised there was no way to answer it.

The atmosphere darkened. For a moment, I thought they might get up and attack me. (Reilly’s a big man who looks like he’s been in a few punch-ups; and Coogan had a dangerous look about him. I’m a big man, but I’m in bad shape*. I wouldn’t have fancied my chances.) Time seemed to have slowed down. Actually it had only been a second or two since I’d spoken.

‘Just kidding!’, I said lamely, smiling and making the universal peace gesture of outward palms. They seemed to relax a bit. ‘It’s nice here, isn’t it’, I added even more lamely, gesturing at the room. (It was a lovely little pub, with excellent food.) They looked relieved, and nodded in agreement. I think one of them said, ‘Yes, it is.’

It was a save, kind of. ‘Bye then!’, I said. I think one of them replied, ‘Yeah, bye’, as I turned and left (not too hastily, I’d like to think).

John C Reilly | Photo: Scott Gries / Getty Images

When I told our party about this awkward encounter, my sister (who’d hosted our meal and had rented our holiday cottage, and consequently felt even more entitled than usual to judge my behaviour) was horrified. Disgusted, even. She said I shouldn’t have done that. Annoyingly, she was right.

🤡

Postscript 1

Laurel and Hardy in the Lakes

I found out that Coogan and Reilly were making a film, Stan and Ollie, about Laurel and Hardy‘s swansong 1953 UK tour. (Oliver Hardy became ill during the tour; he died four years later.) Stan Laurel was born in Ulverston in what’s now south Cumbria. That’s why Coogan and Reilly were in the area.

Apparently Laurel and Hardy attended a civic reception at Ulverston’s Coronation Hall during their 1947 tour. They appeared on the balcony, and waved to a massive crowd in the square below. Laurel was presented with a copy of his birth certificate.

I thought that maybe the BBC film had spliced that event into the 1953 tour, and used Broughton-in-Furness as a stand-in for early 50s Ulverston.

The next day, we saw a film crew in the square in Broughton-in-Furness (a small market town north of Ulverston). My sister thought she saw UK film and TV actor (and former Dr Who) Christopher Eccleston; and she overheard a technician in a shop complaining that he’d been waiting eight hours for a two-minute shoot. Show business!

However, Eccleston wasn’t filming Stan and Ollie, but was making a new series of Cumbria-set BBC drama The A Word. It was a coincidental glut of celebs (but, sadly, my sister didn’t accost Eccleston).

As it happens, Coogan and Reilly weren’t there to film Stan and Ollie either. Apparently, the film, due to be shot largely in the West Midlands and Bristol, had been delayed, and Coogan and Reilly took the opportunity to secretly visit the Laurel and Hardy museum in Ulverston. Apparently, Coogan has a holiday home near Coniston. Nice.

Anyway, I wish I’d known about the Stan and Ollie film at the time of my encounter with Coogan and Reilly. I could have attempted a brief, intelligent conversation about their project, instead of making my would-be-humorous interjection. I could have said, ‘It’s Laurel and Hardy, isnt it?’

Oh well. You always think afterwards about how an unsatisfactory encounter could have gone better. At least I didn’t ask for a selfie. I should have done, really.

The film, released in the UK in January 2019, got 93% on Rotten Tomatoes, and 75% on Metacritic. Not bad. One critic said, ‘You feel like you’re beholding the real duo, so thoroughly concieved are the actors’ physicality and performances’. I thought it was really good. To my new almost-acquaintances Steve and John, I say: well done – just not well met.

🤡

Postscript 2

Steve Garbo – the curse of fame

According to Wikipedia, Coogan likes to keep himself private, and has said ‘I have never wanted to be famous’.

Coogan’s proactive contribution to the UK Leveson Inquiry into illegal press intrusion was admirable and effective. His legal team forced an uber-hacker to say who instructed him to hack Coogan. Coogan got hundreds of thousands of pounds in damages from Mirror Group Newspapers after they – eventually – admitted hacking phones and covering up unlawful activities. (Kerching!)

But, ‘never wanted to be famous’? Really?

What did he think would happen when he worked hard to become a very successful TV comedian and film actor? If you succeed at that, you get famous. Job satisfaction, awards and peer-approval are all very well, but in that line of work fame is a true measure of your success. If Coogan ‘never wanted’ to be famous, he could have done something else.

Sensitive creatives who complain about fame probably did want it – craved it, even – but then couldn’t cope with it when they got it. That’s fair enough, but when they then publicly complain about their fame, it grates with the audience whose appreciation gave it to them.

Anyway, sorry, Steve, for adding my own rubbish intrusion. (I’ve emailed him via his production company, and invited him to read this. I don’t suppose he will, but you never know.)

🤡

Postscript 3

Beverly and Alan – a happy coincidence

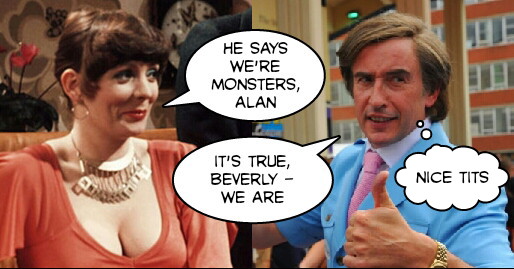

It occurred to me that Mike Leigh and Steve Coogan have something in common apart from me having seen them both in the flesh. They both created brilliant but monstrous comic characters who expose the terrible cracks in the facade of working-class upward mobility.

Leigh’s unforgetable Beverly Moss, wonderfully co-created by actor Alison Steadman (then Leigh’s wife) in his 1977 TV play Abigail’s Party, and Coogan’s local radio/TV presenter character Alan Partridge, co-created with writers Patrick Marber and Armando Iannucci, who first appeared in 1991 and is still going strong, have both deservedly become cultural icons.

Leigh’s roots are middle class and Coogan’s are working class. Leigh’s been accused of middle-class mockery and Coogan could be accused of working-class self-mockery, or, even worse, class betrayal.

(Yon Alan Partridge character is nowt but a lickspittle mockery, an’ a betrayal o’t’ working class an’ our rightful aspiration to better ourselves. Get thee gone, Steve lad, an’ never darken our door again.)

However, such criticism misses the point: the characters are funny because they’re true – exaggerated and enhanced, but fundamentally true. In both cases, the humour’s cruel but not mocking – or betraying.

The characters’ vulnerabilities and pretentions – and their crucial lack of self awareness – are shown with painfully funny honesty.

(Sadly, Leigh and Coogan are not thought to be collaborating on anything any time soon.)

Alison Steadman as Beverly Moss | Photo: BBC

Steve Coogan as Alan Partridge | Photo: Steve Adams

🤡

Please feel free to comment…

I think this post is brilliant – but I wrote it. What do you think? Anything?

LikeLike