Rolling post, begun April 2016

Last: November 2022 | Contents

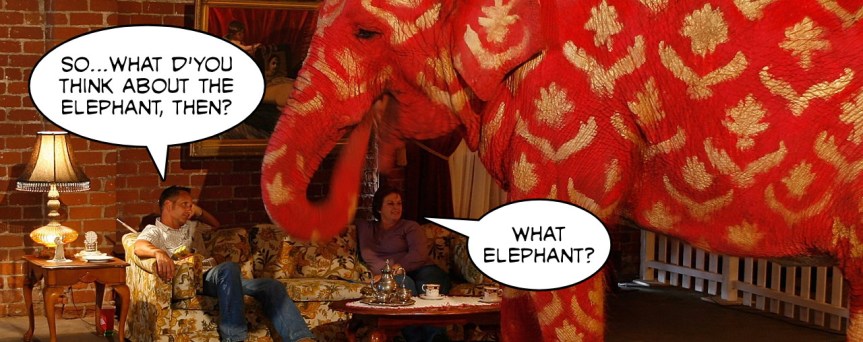

In which, as a remain voter, I detail the metrocentric liberal elite’s arrogant dismissal of white working-class leave voters’ concerns about EU free movement of people as provincial racism. Metrocentric Labour party leaders overlooked the elephant in the room and it cost the party in lost votes.

Guardian letters: January 2017, April 2017, June 2017, June 2017, December 2018, January 2019, December 2019 and September 2023 (Chris Hughes)

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Top 🔼

Contents

2017 🔽 | 2018 🔽 | 2019 🔽 | 2020 🔽 | 2022 🔽

2016

April 2016 | Introduction

May 2016 | Entered the elephant

May 2016 | Labour’s ‘horrible racist’ row

23 June 2016 | Referendum result and immigration

October 2016 | Post-result toxicity

October 2016 | May tackled immigration – accused of xenophobia

December 2016 | By-election blues for Labour

December 2016 | Welsh leader: Labour’s ‘London-centric’ view of immigration could lose votes

December 2016 | Top Labour MP: immigration class divide – shadow home secretary: wrong

bbb

Contents 🔼

2017

January 2017 | Ukip’s post-Farage farrago of fiascos disadvantaged the dispossessed

January 2017 | Corbyn waffled about free movement

March 2017 | Shadow home secretary: Labour must defend free movement

April 2017 | May called snap general election

April 2017 | Starmer: Labour would end free movement

May 2017 | Corbyn said it: free movement to end

June 2017 | Labour manifesto: free movement to end

June 2017 | May lost majority

July 2017 | Labour weaved this way and that

July 2017 | Tory cabinet’s free movement squabble

August 2017 | Labour remainers: defend free movement

August 2017 | Tories got it together, sort of

August 2017 | Labour went soft again

September 2017 | Kofi Annan stuck his oar in

September 2017 | Labour remainers organised to defend free movement

September 2017 | Corbyn to TUC: free movement to end

September 2017 | Government U-turn

September 2017 | Labour stayed in one piece

October 2017 | Conservatives swerved back to Brexit

October 2017 | Tory minister’s ‘tantrum’ smear

December 2017 | Labour wanted ‘easy movement’

bbb

Contents 🔼

2018

March 2018 | May surrendered to Barnier

March 2018 | Labour’s position: no one knew

May 2018 | Tories planned free movement lite

June 2018 | Tory minister backed free movement

July 2018 | Chequers white paper: free movement to end

September 2018 | Abbott immigration speech: nothing on free movement

September 2018 | Belfast legal report: the Irish back door

September 2018 | Migration report: ‘End free movement’

November 2018 | Draft withdrawal agreement – free movement to continue during implementation

November 2018 | Draft political declaration: free movement to end – draft documents approved by EU

December 2018 | Plan B touted: ‘Norway plus’ (includes free movement)

December 2018 | May cancelled vote on Brexit deal – then survived Tory confidence vote

December 2018 | May: withdrawal agreement vote in January – Corbyn: no confidence

December 2018 | Immigration white paper: free movement to end, kind of

bbb

Contents 🔼

2019

January 2019 | ‘Failing’ Grayling succeeds – in backing the end of free movement

January 2019 | Corbyn: free movement negotiable

January 2019 | Pre-vote summary: the DWA, the DPD and free movement

January 2019 | May lost Brexit deal vote – Corbyn lost no confidence vote

January – July 2019 | May resigns – Johnson becomes PM

September – October 2019 | Revised deal agreed – general election arranged

September 2019 | Labour conference voted for free movement

November 2019 | Labour manifesto unclear on free movement

bbb

Contents 🔼

2020

January 2020 | Chickens came home to roost – Labour lost its heartland

January 2020 | Labour abandoned its heartland – again

April 2020 | Metrocentric remainer is new Labour leader

June 2020 | Labour review of 2019 election defeat didn’t mention elephant in room

bbb

Contents 🔼

2022

November 2022 | Bonzo gone; red wall goes off Tories; Starmer: free movement over

Footnote | A brief history of the UK’s brutal colonisation of Ireland, and its troubled aftermath

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

April 2016

Introduction

In the UK in 2016 we were facing a referendum on membership of the EU. Disturbing reports about the high number of rough sleepers in London could be seen to make a good case for the UK leaving.

Most of the rough sleepers were from eastern Europe, part of the recent unrestricted mass immigration to the UK allowed under the EU freedom of movement rule.

Some were working but unable to afford accommodation and not yet eligible for government support. Many were not working. Some had apparently been bussed in by criminal gangs to beg on the street. The police were having to deal with complaints of antisocial behaviour. There were reports of public urination and defecation.

The referendum was happening because Conservative prime minister David Cameron had been pressed by Eurosceptics in his party (and by Conservative MPs worried about their seats being threatened by the rise of the populist anti-EU Ukip party) to put it in his manifesto for the 2015 general election.

Cameron probably didn’t want the referendum. Following his (lacklustre) Conservative-Liberal coalition term of government, polls led Cameron to expect another coalition with the Liberal Democrats. They’d have blocked the referendum.

When he unexpectedly won a majority in 2015 with the un-polled votes of ‘shy’ Conservatives (shy leavers?), Cameron tried to avert the referendum by negotiating better terms for the UK with the EU.

Cameron’s negotiations, typically lacklustre, failed. The referendum, which Cameron had never wanted and had never expected to have to implement, was arranged to take place in June 2016.

As a middle-class left-liberal-Green, I had mixed feelings about the EU. I loved the noble internationalist free-trade idea, but disliked the corrupt neo-liberal bureaucratic gravy-train reality.

In my local café, here in the UK’s East Midlands, I heard the views of two older working-class white women about the EU freedom of movement rule.

They were reluctant to say so, aware their views might be considered ‘wrong’, but they deeply resented this change, imposed with no consultation. Their quiet, genuine and non-racist strength of feeling made a big impression on me.

What did the UK think would happen when they gave EU freedom of movement to poor east European member countries? Why didn’t the UK restrict access until those countries’ economies had risen to western levels – like Germany did (and still does)?

East European immigrants who weren’t sleeping rough in London were gathering in ghettos elsewhere, mostly working and paying tax, but seen as lowering wages, and putting stress on services such as schools and hospitals.

Economic evidence suggests migrants make a positive contribution to the public purse and public services. However, perhaps people’s perception to the contrary arose from a direct experience of unfair competition for scarce resources.

Also, since before the referendum, non-EU immigration had been consistently higher than EU immigration. So why had EU immigration become such a contentious issue? Perhaps because most non-EU immigrants needed a visa; whereas most east European immigrants (mostly low-skilled workers and many with no jobs to come to) were allowed almost unrestricted entry to the UK .

This was breeding resentment amongst the indigenous white working class, whose traditional support for Labour was being transferred to Ukip. The media debate on the referendum was all about trade and jobs, but the elephant in the room was east European immigration.

People were reluctant to say what they thought about free movement for fear of being considered racist (or – just as bad, in some circles – politically incorrect).

There probably was racism at play here, but much of the blame for it lay with government. Mass immigration imposed without consultation was bound to provoke racism.

(We’re probably all potentially racist, but with awareness we can choose not to indulge it – whatever the provocation. See my analysis of racism, Racism explained as a redundant instinct.)

In any case, the referendum would be a secret vote!

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

May 2016

Entered the elephant

With the referendum date in sight, east European immigration was in the news, as figures for EU immigrants were hotly disputed.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

May 2016

Labour’s ‘horrible racist’ row

(The Guardian print newspaper didn’t report this, despite a full report on the Guardian website.)

Labour shadow Europe minister Pat Glass had been pre-referendum door-knocking in Sawley, Derbyshire with a BBC local radio reporter. Thinking she was off-mic*, she said: ‘The very first person I come to is a horrible racist. I’m never coming back to wherever this is.’

The BBC said the man she was referring to later denied being a racist, but said in his conversation with the MP he’d spoken about a Polish family in the area who he thought were living on benefits, and whom he’d described as ‘spongers’.

Glass’s lazy, right-on metrocentric view showed how she and her bien-pensant political class had ignored – and belittled – the genuine concerns of the white working class about east European immigration. Labour, with its unconvincing remain campaign, ignored those concerns at the risk of losing support.

Glass later issued a grovelling apology (well, semi-grovelling – note the weaselly use of the bolded word ‘any‘), saying:

‘The comments I made were inappropriate and I regret them. Concerns about immigration are entirely valid and it’s important that politicians engage with them. I apologise to the people living in Sawley for any offence I have caused.’

Glass was promoted to the post of shadow education minister in June 2016, but resigned two days later. She stood down at the 2017 general election, citing the ‘bruising referendum‘ as a major cause. It’s unfortunate rising star Glass tripped over that ‘bruising’ reality. If she – and her party – had been more aware of the genuine concern about EU mass immigration amongst their voters, Glass might still be an MP.

(* Another off-mic racism-related post-interview comment is described in my blogpost about Aung San Suu Kyi and Myanmar’s persecuted Rohingya Muslims, Halo Goodbye, Suu – the Rohingya crisis. Suu Kyi made a racist off-air comment about BBC Today presenter Mishal Husain after losing her temper during a radio interview when Husain repeatedly asked her to condemn anti-Muslim violence. After the interview, Suu Kyi was heard to say: ‘No one told me I was going to be interviewed by a Muslim.’)

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

23 June 2016

Referendum result and immigration

Metrocentral London: Remain

Most of the rest of country: Leave

(Me: Undecided, but voted: Remain)

The high turnout (72%) and the leave result (disconcertingly close at 52-48%) were unexpected.

It’s estimated 24-30% of Labour voters voted leave.

Immigration was a major factor. Postwar mass immigration from UK colonies and former colonies and the more recent unrestricted free movement of people from Eastern Europe that followed 2004’s EU enlargement were allowed by governments for economic reasons with no consideration for the social wellbeing of either the immigrant or the host communities – and with no public consultation.

The EU referendum was, in effect, the first public consultation on immigration. Several polls confirmed immigration was a main reason for voting leave:

- An Ipsos MORI poll taken just before the referendum showed immigration was seen as the biggest issue (48%) that would influence people’s vote. (The economy scored 27%.)

- A Lord Ashcroft post-referendum poll found 33% of leave voters said the main reason was that leaving offered the best chance for the UK to regain control over immigration and its own borders. (Immigration was second. The highest scoring reason was sovereignty, at 40%.)

- A July 2016 Economist analysis concluded high numbers of migrants didn’t bother Britons, but high rates of change did.

- An April 2018 CSI poll found 40% of leave voters gave immigration as the main reason.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

October 2016

Post-result toxicity

The post-referendum debate turned toxic as metrocentric remainers railed against leave voters, whining stridently about the supposedly stupid people who’d ignored their expert advice.

The poor white leavers, they said, were like Trump supporters, incoherently attacking the establishment like, they implied, a zombie mob shuffling out of their northern housing estates towards the ivory towers of metroland.

But the metrocentrics were the stupid ones. They contemptuously dismissed the leave vote as an incoherent act of general resentment. But the leave vote was about issues – issues the metrocentrics, in their lofty arrogance, chose to ignore.

An April 2018 CSI poll asked leave voters to rank four reasons for voting leave. The poll report said:

‘Interestingly, “To teach British politicians a lesson” had by far the lowest average rank, being ranked last by a full 88% of leave voters. This contradicts the widespread claim that Brexit was a “protest vote”: i.e., people voted leave as a way of venting deep-seated grievances.’

(The CSI poll found immigration was the main reason for voting to leave. It was ranked first of the four reasons by 40% of leave voters polled.)

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

October 2016

PM May tackled immigration – accused of xenophobia

Despite having promised to stay on whatever the result, UK prime minister David Cameron resigned after the referendum. He was replaced as leader of the Conservative Party and as PM by Theresa May.

May had campaigned for the UK to remain in the EU, but now promised to implement the leave result. At the post-referendum Conservative Party conference, she acknowledged the immigration elephant in the room, and confronted the metrocentric sneerers.

Pledging to crack down on immigration, May said some people don’t like to admit British workers can be out of work or on low wages because of low-skilled immigration.

Predictably, leading metrocentrics lashed back. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn said May was fanning the flames of xenophobia and hatred. SNP leader and Scottish assembly first minister Nicola Sturgeon said May’s speech was the most disgraceful display of reactionary right-wing politics in living memory.

Admittedly, May had form. In her previous post as home affairs minister she implemented a Gradgrind approach to reducing immigration. She set ambitious targets which she then failed to meet. An excellent November 2018 Irish Times article links that policy to her post-referendum enthusiasm for ending free movement.

In 2010, home secretary May promised to cut net immigration. Instead it rose significantly. In 2012, she pledged to create ‘a really hostile environment for illegal migrants‘ and wrongly blamed the Human Rights Act for being unable to go further, earning a rebuke from senior judiciary. She ignored warnings about passport backlogs and chaos at border posts, and put ads on the side of lorries telling people to ‘Go home or face arrest‘. The ads were banned for inaccuracy – very few people could actually be arrested – and because of general public revulsion.

It was May’s incompetent and target-led ‘hostile environment’ that led to the shameful cruelty of the Windrush scandal.

So metrocentrics Corbyn and Sturgess arguably had reason to criticise May’s stance on immigration. However, they pointedly failed to acknowledge that this time, May was also voicing the feelings of Leave voters – many of whom were not Conservative voters – who weren’t necessarily xenophobic, but were genuinely concerned about having mass immigration imposed on them.

(If those influential metrocentrics stopped defending their moral high ground, got off their high horses, and got down to thinking about improving society, they might consider that the problems and concerns experienced by the increasingly large precariat underclass could be resolved by paying all adult citizens an unconditional state income. This would, of course, require effective border control – which we could now have. See my post, Robots could mean leisure.)

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

December 2016

By-election blues for Labour

The chickens came home to roost at a by-election in deep-Brexit Lincolnshire. Having previously come second in this safe Conservative seat, Labour trailed fourth – behind Ukip.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

December 2016

Welsh leader: Labour’s ‘London-centric’ view of immigration could lose votes

Welsh assembly first minister Carwyn Jones, the most powerful Labour politician in government, disagreed with the position of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn and shadow home secretary Diane Abbott, who’d defended freedom of movement.

In a Guardian article, Jones said:

‘The danger is that’s a very London-centric position. That is not the way people see it outside London. London is very different: it is a cosmopolitan city and has high levels of immigration. It has that history. It is not the way many other parts of the UK are.

‘People see it very differently in Labour-supporting areas of the north of England, for example. We have to be very careful that we don’t drive our supporters into the arms of Ukip. When I was on the doorstep in June, a lot of people said: ‘We’re voting out, Mr Jones, but, don’t worry, we’re still Labour.’ What I don’t want is for those people to jump to voting Ukip.’

Exactly. (Except they already were.)

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

December 2016

Top Labour MP: immigration class divide – shadow home secretary: wrong

Labour cracks widened on the tricky subject of immigration. Leader Jeremy Corbyn continued to downplay the issue (even as Labour voters continued to drift towards Ukip), but some senior Labour politicians focussed on it.

They included northern Labour MP and political big beast Andy Burnham, former shadow home secretary and the then front-runner for the post of elected mayor – which he subsequently won – of northwest UK region Greater Manchester. Burnham joined Carwyn Jones (see above) in speaking up on the subject.

Writing in the Guardian, Burnham said Labour’s collective failure to tackle concerns over jobs, wages, housing and education linked to migration contributed to the loss of the referendum.

Burnham spoke of a ‘growing class divide‘, with middle-class Labour remain voters looking down on those who voted leave as ‘uneducated or xenophobic‘.

(That’s what I said.)

Stubbornly metrocentric Labour shadow home secretary and close Corbyn ally Diane Abbott then said Burnham had got it back to front, and was wrong.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

January 2017

Ukip’s post-Farage farrago of fiascos disadvantaged the dispossessed

The only good thing, from Labour’s point of view, was that Ukip, the party most likely to benefit from Labour’s metrocentric stance, was disintegrating following the resignation of leader Nigel Farage (the man the metrocentrics – with some reason – loved to hate).

However, this was a bad thing from the point of view of the dispossessed underclass. Ukip, under Farage’s effective leadership, boosted the Conservative Eurosceptic pressure that forced then prime minister David Cameron to promise the referendum. An effective Ukip could have maintained the necessary pressure to ensure the intentions of leave voters were honoured.

Prime minister May seemed to mean well, but without the pressure an effective Ukip could have provided, she was at risk of followeing Cameron into the Brexit bin. Metrocentric remainers would then be free to dilute and delay the process until only a dog’s dinner was left.

However, May held firm. In January 2017 she announced Britain would leave the single market (the subject of much anguished hand-wringing amongst remainers) in order to control and strengthen sovereignty.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

January 2017

Corbyn waffled about free movement

In a major Brexit speech, UK Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn further toned down his already weak statement that Labour was ‘not wedded’ to free movement by adding that it hadn’t been ruled out.

According to an extract handed out the night before the speech – in leave-voting Peterborough – Corbyn was due to say he supported ‘reasonable management‘ of immigration after Brexit. That sounded like something that would happen after the end of free movement (ie, the end of unmanaged immigration). Corbyn was also due to say: ‘Labour is not wedded to freedom of movement for EU citizens as a point of principle.’

That was weak and weaselly. ‘Not wedded to the principle’? (Who wrote that?) Corbyn could just have said Labour’s position was that free movement would end. (He eventually did so in May 2017, before the general election. See below.)

Nevertheless, some thought this was a change of policy by Corbyn, who’d been under pressure from Labour MPs to address the concerns of Labour supporters and swing voters who’d voted leave.

However, in a round of interviews before the speech Corbyn insisted ‘it’s not a sea change at all’ – and complained his planned statement had been misinterpreted.

In the actual speech, after acknowledging many people had expressed deep concern about unregulated migration from the EU, Corbyn said:

Labour is not wedded to freedom of movement for EU citizens as a point of principle, but I don’t want that to be misinterpreted, nor do we rule it out.

[Labour Party’s punctuation]

Corbyn went on to say EU immigration should be part of the negotiated attempt to keep full access to the EU single market.

Right. That was clear, then. As everyone knew by then, full access to the single market would mean accepting – as non-EU Norway does – EU free movement of people.

So, no misinterpretation possible after that gem of clarity, Jeremy.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

March 2017

Shadow home secretary: Labour must defend free movement

Adding to the confusion, the opposition Labour party’s shadow home affairs minister called for free movement to be defended, in apparent contradiction to her party leader’s (apparent) position (see above).

In a widely publicised foreword to a book of essays, Free Movement and Beyond – Agenda Setting for Brexit Britain, Labour’s stubbornly metrocentric shadow home secretary, Diane Abbott, said freedom of movement was a workers’ right.

In her foreword, Abbott described criticism of EU free movement as reactionary and anti-immigrant. She said the labour movement couldn’t accept the attack on freedom of movement, and must stand to defend it.

Abbott, whose parents were Jamaican immigrants, clearly cares deeply about historical and recent injustices suffered by immigrants, but she showed no understanding of the concerns of leave voters about unrestricted immigration from poor east European countries under EU freedom of movement.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

April 2017

May called snap general election

UK prime minister Theresa May was on course for a sensible Brexit, having cruised past various remain obstacles, when she unexpectedly called a snap general election.

She said it was needed to ensure a smooth Brexit, but probably the real reason was that she wanted to take advantage of her party’s big polling lead before the economy – heading for higher inflation and depressed wages – tanked.

Ukip, having achieved Brexit, seemed to have vanished up its own arse, so dispossessed former Labour voters who wanted control over immigration would have to vote – Conservative!

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

April 2017

Starmer: Labour would end free movement

The UK opposition Labour Party said they’d accept the referendum result, and would end free movement. That was big of them.

Labour shadow Brexit minister ‘Sir’ Keir Starmer (human rights lawyer, London MP and arch-remainer) said (presumably through gritted teeth) Labour would seek to end free movement. He added that Labour wouldn’t shut the door on the single market, the customs union or participation in EU agencies.

Despite Starmer’s controversial rider, that was clearer than his leader’s mystical miasma of a pronouncement in January.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

May 2017

Corbyn said it: free movement to end

Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the UK opposition Labour Party, said for the first time that under Labour the free movement of citizens between the UK and the EU would end with Brexit.

In January 2017, Corbyn said in a speech, somewhat cryptically, Labour wasn’t wedded to free movement but it hadn’t been ruled out.

Since then, the prospect of a general election seemed to have concentrated Corbyn’s mind – somewhat, if not wonderfully. He was asked in a TV interview what immigration controls Labour would implement. After some characteristic waffling, Corbyn said:

“Clearly the free movement ends when we leave the European Union but there will be managed migration and it will be fair.”

This confirmed what shadow Brexit minister Keir Starmer said in April (see above). Corbyn and Starmer were both said to favour free movement, but had apparently been persuaded to accept that it must end – to keep Labour and swing-vote leavers sweet. Hence the gritted teeth through which Corbyn’s and Starmer’s concessions were made.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

June 2017

Labour manifesto: free movement to end

The snap general election called by UK premier Theresa May had the benefit of clarifying the opposition Labour party’s position on free movement.

The 2017 Labour manifesto, in chapter 2, Negotiating Brexit, under the heading of Immigration, said:

‘Freedom of movement will end when we leave the European Union.’

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

June 2017

May lost majority

UK Conservative premier Theresa May won her snap general election, getting more seats in parliament than Labour, but she unexpectedly lost her overall parliamentary majority. (Her general election campaign was rubbish, and Labour’s under Jeremy Corbyn was good.)

May managed to get the support of the Democratic Unionist Party, a tiny party in UK country Northern Ireland, to give her a small but workable majority. The DUP wanted a ‘soft’ Brexit, including a ‘soft’ land border with NI neighbour and EU member-state Ireland. (See footnote). An extra £1bn of spending for NI was part of the deal.

May also needed the parliamentary support of every Tory member, including the many EU remainers.

With Brexit negotiations due to begin very soon, May’s pre-election ‘hard’ Brexit plan looked likely to be abandoned – and white working class concerns about mass EU immigration seemed once again in danger of being ignored.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

July 2017

Labour weaved this way and that

Jeremy Corbyn, still leader of the Labour Party after his unexpectedly good performance in the general election, surprisingly announced Labour would leave the EU single market.

This was a change from his previous statement that Labour would push to maintain full access to the single market.

Metrocentric remainers who wanted the UK to stay in the single market – or who simply wanted to derail Brexit – dominated the vocal section of the party. Perhaps Corbyn was thinking of the silent traditional Labour voters who voted leave because of their concerns about recent mass immigration.

Maverick Labour shadow trade minister Barry Gardiner, a remainer in the referendum, but who thought the result must be honoured, then wrote a Guardian article backing Corbyn and explaining why: people voted leave because they wanted UK borders controlled.

However, Labour metrocentric remainer MP and nobody Heidi Alexander in a Guardian.com article said Gardiner’s position was wrong, depressing and disingenuous. Alexander’s views were then reported by the Guardian in the print edition as ‘news‘.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

July 2017

Tory cabinet’s free movement squabble

After UK premier Theresa May’s disastrous snap election, her power had weakened. While she was on holiday, having left no deputy in charge, her ministers were squabbling about Brexit – and about free movement.

Finance minister and arch-remainer Philip Hammond said there should be no immediate change to immigration rules when Britain left the EU.

Trade minister and Brexiter Liam Fox said allowing free movement after Brexit would not keep faith with the referendum result. He said the government had not agreed on whether to keep free movement for a transitional period.

A spokesman for May then stepped in to say free movement would end in March 2019.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

August 2017

Labour remainers: defend free movement

A Guardian report said Labour remainer MPs including Clive Lewis and David Lammy had written an open letter calling for Labour to defend free movement.

The report said although Labour’s official position was that free movement would end at the point of Brexit in March 2019, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn and his shadow home secretary Diane Abbott had always supported free movement.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

August 2017

Tories got it together, sort of

After the June general election, weakened prime minister Theresa May couldn’t purge her cabinet as she’d planned. Finance minister and arch-remainer Philip Hammond escaped the chop – and had been making trouble.

However, all was now sweetness and light as Hammond collaborated with trade minister and arch-Brexiter Liam Fox to write a newspaper article meant to mend fences.

There’d been much discussion about a ‘transitional period’ after Brexit, with some remainers suggesting a minimum five-year period, during which free movement would continue.

In their joint article, Beavis and Butt-Head announced a time-limited transition period. They also made it clear that after Brexit in 2019, the UK wouldn’t be in the single market or the customs union.

Needless to say, liberal remainers objected to this sensible announcement. However, May’s ‘hard’ Brexit – amazingly – seemed to be back on track.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

August 2017

Labour went soft again

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn swerved dramatically to the metrocentric remainer ‘soft’ Brexit side when he allowed his shadow Brexit minister Keir Starmer – a London MP and human rights lawyer – to announce that Labour wanted a two-to-four-year transition period after Brexit, during which the UK would fully participate in the EU single market and customs union.

This was the same Jeremy Corbyn who one month ago (see above) announced that Labour would leave the single market after Brexit.

Participation in the single market would mean accepting free movement. In April 2017, Starmer said Labour would end free movement, but Labour’s new policy would mean up to four years more of free movement after Brexit – possibly until 2023.

With Ukip in shreds, many Labour leave voters who wanted to end free movement would probably now vote Conservative in the next general election, due in 2022.

Apparently, Corbyn – MP since 1983 for Islington North in the trendy north London heartland of metrocentricity – was happy to abandon those traditional Labour voters in the Midlands and the North.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

September 2017

Kofi Annan stuck his oar in

Influential Nobel Peace Prize winner and former UN secretary general Kofi Annan (on a flying visit from his Swiss HQ to northern UK city Hull to give a lecture) said in an interview with UK metrocentric national newspaper the Guardian the UK should continue EU freedom of movement after Brexit.

Waffling meaninglessly about ‘choice‘, the formerly great man exposed his woefully inadequate understanding of the referendum result.

Annan needed to look at his own recent choice: to head a toothless commission of inquiry into Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslims. The commission produced a report full of good advice which was effectively shelved by the Myanmar government. It was clearly a cynical attempt to deflect international criticism from formerly saintly fellow Nobel Peace Prize winner and now badly compromised Myanmar government head Aung San Suu Kyi.

(See my rolling blogpost on that subject, Halo Goodbye, Suu – the Rohingya crisis.)

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

September 2017

Labour remainers organised to defend free movement

A group of pro-EU Labour MPs and activists launched the Labour Campaign for Free Movement.

Their aim was to reinforce Labour’s recent swerve to a soft Brexit. The campaigners had drafted a resolution for the Labour conference, backing the continuation of free movement. They were encouraging local Labour parties to support the resolution.

An article backing the campaign on centre-left website LabourList by prominent Labour leftie Hugh Lanning apparently committed the campaign to free movement from everywhere – not just from the EU!

Left-wing website Left Futures (edited by Momentum founder Jon Lansman) ran a piece by teacher and writer David Pavett effectively demolishing the weird logic of Lanning’s article and the free movement campaign.

The main campaign backers were:

- Clive Lewis, close Corbyn ally and shadow minister whose constituency in Norwich was an island of remain in Norfolk’s sea of leave

- David Lammy, London MP who in 2016 urged Parliament to overrule the referendum

- Manuel Cortes, London-based union leader

- Tulip Siddiq, London MP

They all had a personal stake in free movement:

- Lewis’s father emigrated to the UK from Grenada.

- Lammy’s parents emigrated from Guyana.

- Siddiq spent most of her childhood in Bangladesh. (Controversial Bangladeshi prime minister Sheikh Hasina Wazed is Siddiq’s aunt.)

- Cortes moved to the UK from British overseas territory Gibraltar to undertake further and higher education and forge his career.

Fair enough. However, they apparently had no understanding of the concerns of poor working class traditional Labour voters about the unrestricted immigration of even poorer east Europeans.

As Lewis had mixed heritage, Siddiq was South Asian, Lammy was black and Cortes was Spanish, they’d have experienced personal and institutional racism and xenophobia, and would have beeen sensitive to the element of racism in white Labour voters’ opposition to free movement.

However, they should have respected those people’s very real non-racist concerns and anxieties about free movement – concerns which made them vote leave.

In 2016 Lewis said:

‘…free movement of labour hasn’t worked for a lot of people. It hasn’t worked for many of the people in this country, where they’ve been undercut, who feel insecure’.

Lewis’s solution was for employers who brought in EU workers to be obliged to negotiate with a trade union to ensure wages of local workers weren’t undercut. But he’d apparently abandoned his support for the insecure precariat in favour of blanket metrocentric remainer obstructionism.

The Labour Party, having thus far survived the Corbyn crisis, might well have fallen apart over this issue, as both sides of the free movement divide dug in.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

September 2017

Corbyn to TUC: free movement to end

UK opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn confirmed free movement would end on leaving the EU. At the September 2017 annual UK Trades Union Congress (TUC) conference, Corbyn said:

‘When we leave the EU, the current free movement rules will end.’

It wasn’t clear what views – if any – trade unions collectively held on freedom of movement, or how that might have affected the Labour Party. The party was partly created (in 1900) by trade unions, which kept close links with the party and provided about half its funding through ‘affiliation‘.

Affiliation to the Labour Party used to give unions a block vote on policy and leader selection. The block vote for leadership elections was abolished in 1994, but lived on at the party conference (where votes were split 50:50 between union delegates and constituency Labour parties).

In February 2018, two of the biggest UK unions signed a Brexit statement which called for the UK to stay in the EU’s single market and customs union and called on the government to ‘uphold freedom of movement for skilled workers’.

The TUC, a federation (which isn’t itself affiliated to the Labour Party) of most trade unions in England and Wales, apparently preferred staying in the single market and accepting free movement, but applying previously unused EU controls. Its September 2018 Brexit statement said:

‘If the outcome of negotiations with the EU was for the UK to stay in the single market in the longer-term…the UK should look at other EU countries’ models of free movement, and should use all the domestic powers at its disposal to manage the impact of migration.’

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

September 2017

Government U-turn

In a speech in Florence, Italy, UK Conservative prime minister Theresa May turned around on her promise to end free movement when the UK leaves the EU.

In July 2017, May said free movement would end in March 2019, the scheduled date for Brexit.

However in her Florence speech, she now said free movement would continue for two years after March 2019 (albeit subject to a Belgian-style registration process).

May, weakened by her disastrous snap election, was either pandering to Conservative remainers led by finance minister Philip Hammond, or surrendering to unelected EU negotiator Michel Barnier. Or both.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

September 2017

Labour stayed in one piece

The Labour party avoided tearing itself apart over free movement at its annual conference (see above) – by avoiding the subject!

The powerful Corbyn-backing Momentum movement managed to block any debate about Brexit. They apparently thought it would be used to attack their man.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

October 2017

Conservatives swerved back to Brexit

In her recent Florence speech, Conservative UK premier Theresa May said free movement would continue for at least two years after Brexit in March 2019. (See above.)

However, in a speech at the Conservative annual conference, immigration minister Brandon Lewis (a remainer) said freedom of movement for EU migrants would end in March 2019.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

October 2017

Tory minister’s ‘tantrum’ smear

Conservative Europe minister and prominent remainer Alan Duncan insulted leave voters in a speech in Chicago by saying the leave result was caused by campaigners inciting prejudice about immigration. Duncan said leave voters ‘were stirred up by an image of immigration, which made them angry and throw a bit of a tantrum‘.

Multi-millionaire Duncan (who was reprimanded by the House of Commons fees office for claiming more than £4,000 over three years in expenses for gardening, including £600 to maintain his ride-on lawnmower) is MP for leave-voting Rutland and Melton. He might have some explaining to do to his constituents.

Some leave campaigners may have tried to stir up anti-immigrant prejudice. But most leave voters weren’t prejudiced and weren’t so stupid they could be manipulated by bigots.

They had real concerns about unrestricted migration from poor east European countries.

Before unexpectedly switching to the remain side in March 2016, Duncan tried to join the Vote Leave campaign after saying he’d ‘spent 40 years wishing we had never joined the EU’ since voting against membership in the last referendum in 1975.

Before switching, Duncan had said the question of immigration was ‘far more complicated than many have admitted’. Now he’s a remainer, things are much simpler.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

December 2017

Labour wanted ‘easy movement’

Shadow Brexit secretary Keir Starmer said on TV that Labour backed the ‘easy movement’ of EU workers after Brexit and was also prepared to consider ongoing payments. This would ensure, he said, that the UK kept the full benefits of the single market and the customs union.

Remainer Starmer said:

‘The end of free movement doesn’t mean no movement. Of course we would want people to come from the EU to work here, we would want people who are here to go to work in the EU.’

Asked if that was best described as ‘easy movement if not free‘, Starmer replied, ‘Yes, of course’.

Starmer agreed Labour was seeking a ‘Norway-style agreement for the 21st century‘. (The modern aspect was apparently a bespoke customs union.)

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

March 2018

May surrendered to Barnier

In her September 2017 speech in Florence, UK premier Theresa May said free movement would continue for at least two years during the transition period after Brexit in March 2019. (See above.) Then in October, immigration minister Brandon Lewis said freedom of movement would end in March 2019. (See above.)

In her Mansion House speech on 2 March 2018, May confirmed this, saying:

‘We are clear that as we leave the EU, free movement of people will come to an end and we will control the number of people who come to live in our country.’

Then, on 19 March 2018, a draft withdrawal agreement negotiated with unelected EU panjandrum Michel Barnier (and due to be rubber-stamped by the mostly sheep-like 27 member states) said free movement would continue during the transition period until December 2020.

So once again, precariat leave voters had been overlooked and ignored.

Apparently, the continuation of EU rules including free movement was a quid pro quo for allowing us to negotiate trade agreements during transition. That was kind of them.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

March 2018

Labour’s position: no one knew

Meanwhile, did anyone know what the view was of the UK opposition Labour Party and its leader Jeremy Corbyn on free movement?

Debate on the issue at Labour’s annual conference last year was smothered by the powerful Corbyn-backing Momentum movement to prevent it being used to attack their man. (See above.)

in September 2017 (see above), Corbyn told the TUC, ‘When we leave the EU, the current free movement rules will end. Labour wants to see fair rules and management of migration.’

Then in December 2017 (see above), shadow Brexit minister Keir Starmer, Labour’s chief remainer, diluted that commitment by saying on TV that the end of free movement didn’t mean no movement, and Labour would accept the ‘easy movement‘ of workers to secure the benefits of the single market and customs union.

Starmer also said Labour was seeking a ‘Norway-style agreement for the 21st century‘. How modern! However, Norway’s agreement with the EU involves acceptance of free movement.

As a blog writer, I asked Labour’s press office to clarify Labour’s position on free movement. I mentioned this post. They said my query had been forwarded to the office of Diane Abbott – the stubbornly metrocentric shadow home secretary. I had no reply.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

May 2018

Tories planned free movement lite

It was reported that the UK Conservative government planned to offer the EU a post-Brexit immigration plan very similar to current free movement rules. The plan would see a high level of access to the UK for EU citizens in the future, but would let the UK halt it in certain circumstances.

A government insider said civil servants had been looking at how to give the UK-EU talks some momentum, and dealing with this issue was a way to do it.

However, a government spokesperson said news of the offer wasn’t true, and went on to say:

- ‘People voted in the referendum to retake control of our borders, and that is the basis we are negotiating on. After we leave the EU, freedom of movement will end and we will be creating an immigration system that delivers control over who comes to the UK, but that welcomes the brightest and best who want to work hard and contribute.’

This was a clash between Brexit minister David Davis and Olly Robbins, Brexit advisor to prime minister Theresa May. Leaver Davis resented being undermined by a remainer civil servant. May had form for relying on dodgy advice – as in her disastrous 2017 snap election.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

June 2018

Tory minister backed free movement

Greg Clark, UK Conservative business minister, warned prime minister Theresa May that restricting the access of EU workers into the UK after Brexit could be as damaging as a hard trade border. He said firms’ fears that a tougher approach to immigration from Europe would affect their operations were being heard ‘loud and clear’ by his department.

Economist Clark’s concern was apparently about UK service industry workers needing to move freely to work in the EU. The UK service industry was worth 80% of UK gross domestic product.

In order to get those UK service workers into Europe, Clark seemed willing to accept continuation of EU freedom of movement as a quid pro quo. No doubt that would have pleased other industries that had come to rely on cheap imported labour.

Northerner Clark, son of a milkman, couldn’t be accused of ingrained metrocentric elitism. Clark added that not enough time had been spent talking about the movement of people compared to that of goods, following Britain’s exit. That was true.

However, in calling for continued free movement of labour, Clark was arrogantly disregarding the genuine concerns about mass EU immigration that underpinned the referendum result.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

July 2018

Chequers white paper: free movement to end

Following a crunch cabinet meeting at Chequers (during which ministers were required to hand in their mobile phones) Theresa May’s Conservative UK government issued a white paper on Brexit.

The Chequers white paper, under the heading of ‘Immigration’, welcomed the contribution that migrants bring to our economy and society, and went on to say:

‘5.3 However, in the last decade or so, we have seen record levels of long term [sic] net migration in the UK, and that sheer volume has given rise to public concern about pressure on public services, like schools and our infrastructure, especially housing, as well as placing downward pressure on wages for people on the lowest incomes. The public must have confidence in our ability to control immigration. It is simply not possible to control immigration overall when there is unlimited free movement of people to the UK from the EU.

‘5.4 We will design our immigration system to ensure that we are able to control the numbers of people who come here from the EU. In future, therefore, the Free Movement Directive will no longer apply and the migration of EU nationals will be subject to UK law.’

Some aspects of the Chequers agreement upset some cabinet Brexiteers. Political big beast and foreign affairs minister Boris Johnson, and Brexit minister David Davis both resigned.

This was a victory for unelected advisor Olly Robbins. (See above.) Robbins – paid more than the PM – was the key adviser behind the Chequers strategy which led to the resignations of Davis and Johnson. Davis had been working on his own strategy white paper, only to discover May and Robbins had side-lined him.

Needless to say, remainers put the boot in. However, in spite of many difficulties, May stuck to her guns: free movement would end.

EU unelected chief negotiator Michel Barnier was likely to also put the boot in, pompously maintaining freedom of movement was an uncrossable ‘red line’ – despite many EU member states questioning it.

The ‘negotiations’ for a UK-EU deal were an embarrassment. The ‘no deal’ option might cause difficulty and disruption, but would have the benefit of a clean break – and we could take our £40bn football home with us. (The UK might then be sued for the £40bn – but how would the court order be enforced?)

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

September 2018

Abbott immigration speech: nothing on free movement

A speech on immigration by the UK opposition Labour Party’s shadow home affairs minister managed to completely avoid the toxic topic of free movement.

Labour’s stubbornly metrocentric shadow home secretary, Diane Abbott, made a speech in London on 13 September 2018 explaining Labour’s policy on immigration.

In her speech, Abbott announced a reformed work visa policy which would be available to ‘all those we need to come here, whether it is doctors, or scientists, or care workers, or others’.

However, apart from saying ‘anyone who arrived here under the Freedom of Movement provisions up to the exit date must continue to be accorded those same rights going forward’, Abbott’s speech had no reference at all to free movement, whether ending it or – as she previously advocated – defending it.

However, she referred several times to the possibility of immigration being part of a trade deal with the EU, or with others. She said Labour’s immigration policy would be ‘Brexit-ready’:

‘Brexit-ready means that our new system can be applied and can accommodate any new trade agreements. That is an agreement either with the EU itself or trade agreements with other countries…If access by our trade partners – and by us – is needed as part of any trade deal, our system can accommodate it. It will be Brexit-ready.’

Perhaps Abbott was hoping that, although it was apparently still Labour party policy to end her beloved free movement, it might be revived as part of some Frankenstein trade deal.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

September 2018

Belfast legal report: the Irish back door

A report published in Northern Ireland addressed the issue of back-door access for EU immigrants.

Brexit, Border Controls and Free Movement, a policy report by BrexitLawNI (a UK-government-funded collaboration between two university law schools and a human rights organisation), said advocates of further migration controls viewed the region as a potential ‘back door’ to the UK after Brexit.

The report said the UK had ruled out passport controls within the common travel area (CTA) agreed between the UK and Ireland, and intended to rely on UK ‘in-country‘ controls by, for instance, landlords and employers. This is the disastrous ‘hostile’ environment that caused the Windrush scandal.

Given the risk of ‘in-country’ controls being even more pronounced in NI, and given the potential ‘back-door’ problem, the report recommended the CTA be legally underpinned and continued EU freedom of movement into NI and across the CTA should be considered as an option.

However, given the government’s assurance that there’d be no border in the Irish Sea, wouldn’t that have been a front door to continued mass EU migration to mainland UK?

bbb

Perhaps the back door – and the front door – could have been closed by giving Northern Ireland back to the Irish.

Given our brutal history of colonialism in Ireland, it’d be fair to give it back. The self-styled unionists – who want to keep Northern Ireland within the UK, but couldn’t actually care less about the UK – would object for a while, but they’d be fine.

We could have a referendum on it! (Admittedly, it’d be constitutionally challenging. Maybe we could buy the unionist majority out.)

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

September 2018

Migration report: ‘End free movement’

An independent government-sponsored report on the impact of EU immigration to the UK recommended freedom of movement should end.

The report by the migration advisory committee (MAC), EEA migration in the UK: Final report said, in a foreword by MAC chair Professor Alan Manning:

‘…we recommend moving to a system in which all migration is managed with no preferential access to EU citizens.

‘This would mean ending free movement… The problem with free movement is that it leaves migration to the UK solely up to migrants and UK residents have no control over the level and mix of migration. With free movement there can be no guarantee that migration is in the interests of UK residents.’

Manning made it clear his recommendation was based on immigration not being part of the negotiations with the EU and the UK deciding its future migration system in isolation. He apparently accepted ending free movement might be bargained away to get a trade deal.

However, as ending free movement was the current position of the government, the report should have strengthened its negotiating position – and weakened that of pompous obstructionist M Barnier.

Needless to say, business leaders, hooked on cheap east European labour, immediately started squealing. They’d had two and a half years to think about kicking their habit, and their lobbyists had squeezed out a further two-year ‘implementation period‘ during which free movement would pretty much continue. But like the pathetic junkies they were, they were hurting. Bless.

UK prime minister Theresa May was said to be planning to push the MAC report through her cabinet, despite opposition from remainers Philip Hammond (finance minister) and Greg Clark (business minister and lobbyist for the business squealers).

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

November 2018

The Government published a draft withdrawal agreement (DWA) on Brexit, the final result of many months’ ‘negotiations’. The DWA would require the UK to follow EU rules during implementation period. Apparently, this included the free movement of people.

After getting agreement on the draft from her cabinet, UK premier Theresa May said,

‘When you strip away the detail, the choice before us is clear: this deal, which delivers on the vote of the referendum, which brings back control of our money, laws and borders, ends free movement, protects jobs, security and our union – or leave with no deal. Or no Brexit at all.’

May said the deal would end free movement, but the DWA actually made no mention of free movement of people (except in a section on Gibraltar). However, it said the UK would continue to observe all EU rules during the implementation period.

Apparently, May’s claim that the DWA deal would end free movement merely referred to the DWA kindly allowing us to leave after the implementation period, and the UK then being able to take full control of immigration.

Over the last year or so, the government had been consistently inconsistent about exactly when free movement would end.

- In July 2017 (see above), amid cabinet squabbling, a spokesman for May said free movement would end in March 2019.

- In September 2017 (see above), May said free movement would continue for two years after March 2019, albeit subject to registration.

- In October 2017 (see above), immigration minister Brandon Lewis said free movement would end in March 2019.

- On 2 March 2018 (see above), May said free movement would end when we left the EU.

The main stumbling block for the DWA was the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland (yawn). The DWA’s compromised solution could apparently result in the UK being permanently stuck in the proposed temporary customs union.

Despite supposed cabinet agreement on the DWA, this contentious issue led to the resignation of several ministers soon afterwards, including Brexit minister Dominic Raab (who’d replaced David Davis for four short months after Davis’s resignation in July – see above).

A government white paper on immigration, awaited for over a year and supposedly due soon, was expected to say free movement would end.

Unelected panjandrum Michel Barnier, arrogant EU negotiator and obstructionist, was the chief architect of the humiliating DWA. Barnier twisted the knife still further by helpfully suggesting the UK could extend its implementation period by two years, at a cost of about £20bn (on top of the £40bn already agreed).

That would mean four more years of free movement. Merci beaucoup, Monsieur.

May was now – again! – under threat of removal by her own party. Meanwhile, she grimly hung on to the DWA schedule: approval of the DWA by EU states Germany and France and their flock of sheep, followed by a crunch parliamentary vote.

If, as seemed likely (given the opposition to the DWA from almost every side), that vote was to fail, then things would get messy. The options would then include a second referendum, a general election – or ‘no deal‘.

What would ‘no deal’ mean to leave voters concerned about free movement? No pollsters seemed to have asked.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

November 2018

Draft political declaration: free movement to end – draft documents approved by EU

The government published a full and final version of its draft political declaration (DPD) on Brexit. It confirmed their intention to end free movement, but wasn’t legally binding. This and the draft withdrawal agreement (DWA) – which was legally binding – were approved by the 27 other EU states, and then needed approval by parliament.

When the government published its Brexit DWA (see above), they also published a short DPD, which addressed the future relationship between the EU and the UK. They now published a new 26-page version of the DPD.

The DPD had been agreed by negotiators, and needed to be approved – along with the DWA – by the 27 other EU countries at a Brussels summit on 25 November, and then by the UK parliament in December.

The first, seven-page, DPD mentioned free movement just once, under the heading of ‘Security partnership‘. A very long non-sentence proposed:

‘…reciprocal law enforcement and judicial cooperation…taking into account…the fact that the United Kingdom will be a…country that does not provide for the free movement of persons.’

The new – better written – 26-page version didn’t mention free movement under ‘Security partnership‘. (That section merely said, ‘The [security] partnership will respect the sovereignty of the United Kingdom…’).

However, the new DPD mentioned free movement of people twice elsewhere. In the introduction, it said:

‘The future relationship will be based on a balance of rights and obligations …This balance must ensure…the sovereignty of the United Kingdom…while respecting the result of the 2016 referendum including with regard to…the ending of free movement of people between the Union and the United Kingdom.’

More specifically, under the heading of ‘Mobility‘, the new DPD said:

‘Noting that the United Kingdom has decided that the principle of free movement of persons between the Union and the United Kingdom will no longer apply, the Parties should establish mobility arrangements…’

However, the DPD, unlike the DWA was not legally binding. At the end of the implementation period in January 2021, that declared policy – that free movement of people would no longer apply – could be changed.

In spite of Spain having a hissy fit about Gibraltar and vainly threatening to derail EU approval, the EU 27 duly rubber-stamped both documents – the DWA and the DPD – at the summit.

The two documents then needed approval by the UK parliament at a vote due in mid-December. Speculation about what might happen if, as expected, it got voted down spiralled into seeming hallucinogenic madness. Welcome to Planet Panic.

In any case, we were legally bound to leave next March. The EU could allow an article 50 extension for a second referendum – but what would the referendum question be?

Suggested format for a second referendum

Please place a tick next to one of the following statements:

1. I’m an intelligent urban liberal who lost last time, but it wasn’t fair, so I’ve demanded a second referendum, and this time I want the obviously correct result: to stay in the EU.

2. I’m allegedly an ignorant provincial racist who supposedly got it wrong last time, but I haven’t changed my mind – and I resent being asked to vote again.

A new referendum might also address the Brexit Irish ‘question’ by asking: Should Northern Ireland be unified with Ireland? Yes or No.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

December 2018

Plan B touted: ‘Norway plus’ (includes free movement)

As panic increased in the UK political bubble known as Westminster (the London location of parliament) in advance of the vote on UK premier Theresa May’s Brexit ‘plan’, ie, the draft withdrawal agreement (see above) and the draft political declaration (see above), and as wild flowcharts filled newspaper pages, MPs’ thoughts turned to Plan B.

May was holding firm, echoing former UK premier Margaret Thatcher’s ‘There is no alternative’. However, perhaps with May’s tacit approval, some of her cabinet colleagues (including tax-avoiding minister Amber Rudd) had joined with influential Labour MPs (including Europhile Stephen Kinnock) to tout ‘Norway plus‘, a scenario featuring continued free movement.

Norway isn’t a member of the EU but is in the European Economic Area (EEA), meaning it’s part of the European single market. It contributes to the EU budget, and has to follow most EU rules and laws, including the freedom of movement of goods, services, capital – and people.

Norway isn’t part of the EU customs union, so, to avoid a hard Irish border (yawn), a new customs union with the EU – a ‘Norway plus‘ solution – would be needed.

The UK wasn’t in the EEA. To get in, the UK would have to join EFTA – the European Free Trade Association, namely Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Switzerland.

This plan was rejected by Heidi Nordby Lunde, an MP in Norway’s governing Conservative party, and leader of Norway’s European movement. Lunde, claiming her views reflected those of the governing party, said:

‘It is not in my country’s interests to have the UK aboard, and I cannot see how possibly an EEA/EFTA agreement could be in the interests of the UK As part of the agreement with the EU we accept migration and free movement, we have our own body of justice, but it is compliant with the European court of justice. We accept the rules and regulations of the single market.’

Kinnock said the EFTA court could diverge from the European court of justice, and the EFTA treaty allowed for an emergency brake on migration in exceptional circumstances. Not very convincing, Stephen.

Plan Z, anybody? Let parliament:

- Implement previously unused immigration controls, as allowed under EU rules.

- Get a two-month Brexit extension to give time for second referendum.

- Hold a second referendum, and if, as expected (now unrestricted immigration from poor east European countries had been stopped) the referendum delivered a remain majority, then –

- Cancel Article 50 as allowed by a recent EU ruling.

- Er, that’s it.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

December 2018

May cancelled vote on Brexit deal – then survived Tory confidence vote

UK Conservative premier Theresa May called off the crunch vote on her Brexit deal so she could go back to Brussels and ask for changes to it.

May admitted the deal would be rejected by a significant margin if MPs voted on it. She said she was confident of getting reassurances from the EU on the Northern Ireland border plan.

The following day, a confidence vote was triggered by Conservative MPs angry at May’s Brexit policy, which they said betrayed the 2016 referendum result.

May won the vote by 200 to 117 and is now immune from a leadership challenge for a year. Speaking outside her official residence in Downing Street, she vowed to deliver the Brexit ‘people voted for’ but said she had listened to the concerns of MPs who voted against her.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

December 2018

May: withdrawal agreement vote in January – Corbyn: no confidence

UK prime minister Theresa May announced a date for the postponed vote on the EU withdrawal agreement. Opposition Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn then tabled a motion of no confidence in the PM.

A week after cancelling the crunch vote on her Brexit plan, and then surviving a confidence vote by her own Conservative party, UK premier Theresa May announced the postponed vote on the withdrawal agreement would take place in mid-January.

May said she hoped for ‘further political and legal assurances‘ from the EU before the vote in January. She also urged MPs not to ‘break faith with the British people’ by demanding a second referendum.

Opposition Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn said putting off the vote until January was unacceptable. He tabled a motion of no confidence in the PM because of her failure to hold the ‘meaningful vote‘ immediately.

However, the government was able to simply refuse to allow parliamentary time for Corbyn’s motion – because it addressed May personally, not her government. Corbyn’s half-baked motion couldn’t lead to a general election (under the terms of the Fixed Term Parliament Act), so it was just ignored.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

December 2018

Immigration white paper: free movement to end, kind of

The UK government finally published its much delayed ‘white paper‘ on post-Brexit immigration policy. This policy document said free movement would end in 2021 after the implementation period (due to end on 31 December, 2020).

However, business squealers hooked on cheap east European labour and their pusher, business minister and lobbyist Greg Clark, had won a shoddy compromise: free movement lite – until at least 2025.

As a ‘transitional measure‘, unlimited numbers of low-skilled migrants from ‘low-risk countries‘ in Europe and elsewhere would be able to come to the UK without a job offer and seek work for up to a year.

The scheme was designed to fill vacancies in sectors such as construction and social care which are heavily dependent on EU labour and which ministers feared could struggle to adapt when free movement ended.

Poor things. Businesses have only had two and a half years so far, and they’ve only got a further two years up to and during the implementation period. It must be a terrible struggle doing absolutely nothing to adapt to the end of cheap foreign labour – for four and a half years.

The government – split over immigration – had caved in completely to the demands of industry while ignoring the strong public desire expressed in the referendum to end free movement.

The chief winners would be businesses, free to exploit the bonanza of a huge new pool of cheap labour from around the world, while continuing to avoid their responsibility to recruit and train local talent.

Low-skilled immigrants would have to pay an entry fee, wouldn’t get benefits, and wouldn’t be able to bring their family or switch to another migration scheme. There’d be a ‘cooling off period‘ after a year, meaning they’d be expected to leave and not to come again for another year.

However, there’d be no way of making sure people left after a year. Someone obliged to go back to their home country after a year could easily ‘disappear‘ under the radar, and take another low-paid job.

This scheme would continue the main free movement problem: large numbers of low-paid workers from abroad upsetting the locals and undercutting their wages.

Happy Christmas, dear Reader! 🎄

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

January 2019

‘Failing’ Grayling succeeds – in backing the end of free movement

In a bid to boost support from Conservative voters (and, therefore, rebel Conservative MPs) for the Brexit withdrawal agreement (see above) ahead of the postponed crunch vote due on 15 January, loyal cabinet minister Chris Grayling gave a warning in right-wing UK newspaper the Daily Mail that if freedom of movement is allowed to continue, people may turn to extremism.

Brexiter Grayling, nicknamed ‘Failing‘ by left-liberal UK newspaper the Guardian because of his disastrous performance as transport secretary (especially with regard to Britain’s rubbish privatised railways), said:

‘If MPs who represent seats that voted 70 per cent to leave say, ‘Sorry guys, we’re still going to have freedom of movement‘, they [leave voters] will turn against the political mainstream … We would see a different tone in our politics – a less tolerant society, a more nationalistic nation … It will open the door to extremist populist political forces in this country of the kind we see in other countries in Europe.’

He could be right – about that, at least.

Happy New Year, dear Reader! 🥂

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

January 2019

Corbyn: free movement negotiable

Interviewed on BBC TV current affairs programme the Andrew Marr Show, UK opposition Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn said free movement should end, but went on to say it should be negotiable:

‘Many workers that are vital in this country to agriculture, to the care sector, to the NHS and to education have either left or are contemplating leaving. We have 100,000 vacancies in the NHS. Our economy relies on people coming in from other countries. I want to keep that.’

That sounded a bit like the recent government white paper on immigration (see above), which proposed that after Brexit unlimited numbers of low-skilled migrants from Europe and elsewhere could to come to the UK to fill vacancies in sectors such as construction and social care.

Pushed repeatedly by Marr to say whether or not free movement should continue after Brexit, Corbyn eventually said it should be ‘open to negotiation’. Finally, he invoked Labour’s immigration policy, produced by shadow home secretary and stubborn metrocentric Dianne Abbott (see above), saying, ‘Diane Abbott has made it very clear our migration policy will be based on the needs and rights of people to work in this country’.

In her September 2018 speech explaining Labour’s immigration policy, Abbott made no mention of free movement, but emphasised the possibility of immigration being part of a trade deal with the EU, or with others.

Corbyn’s metrocentric waffle on free movement – the transcript

BBC transcript of that part of Corbyn’s interview by Andrew Marr.

(Marr’s aggressive line of questioning indicated under-researched kneejerk liberal-elite support for the free movement of people.)

AM: Let me ask you about another area which is the free movement of people. Why are you against the free movement of people?

JC: I’m not against the free movement of people. What I want to end is the undercutting of workers’ rights and conditions which has increasingly happened in some parts of western Europe, and I did in the referendum actually make quite a lot about the whole issue of what’s called the posting of workers directive on that issue.

AM: But in your own manifesto, not long ago you said, ‘freedom of movement will end when we leave the European Union.’ Why?

JC: Because we would not be in the European Union. We would obviously have an immigration based policy which would be based on the rights of people to move in order to contribute to the economy here. Obviously what’s happened with the uncertainty surrounding Brexit is two things. One is many EU nationals feel deeply uncertain. We would unilaterally legislate straight away to guarantee them all permanent rights of residence in Britain, including the right of family reunion. The second is that many workers that are vital in this country to agriculture, to the care sector, to the NHS and to education have either left or are contemplating leaving. We have 100,000 vacancies in the NHS. Our economy relies in people coming in from other countries. I want to keep that.

AM: It is in your gift right now to say that you would allow the free movement of people from the EU to continue after Brexit. It would make it much easier to negotiate and it’s something you could say and you could do right now.

JC: I think I’ve made it pretty clear the need for workers to go both ways, because obviously there are an awful lot of British workers that work in other parts of Europe. I meet them all the time as I’m sure you do.

AM: But you’re not saying that you would allow free movement to continue?

JC: What we’re saying is that we would want…

AM: Why not?

JC: …we’d want that migration to be able to take place, we’d want those conditions to take place, we would not be part of the European Union if we were outside it, so clearly that…

AM: But you could allow free movement as a non-member of the EU?

JC: It will be open to negotiation but the point has to be about the treatment of EU nationals in this country, which we would radically change straight away. Remember Andy Burnham proposed

AM: You can just say we’re going to end free movement [sic*], why not?

[*Perhaps this was a mistake by Marr or a transcript error. Metrocentric remainer Marr was clearly pushing Corbyn to say he’d allow the continuation of free movement.]

JC: Andy Burnham proposed straight after the referendum to guarantee rights of all EU nationals here. Government voted that down. They ignored the vote in parliament and then opposed it.

AM: I’m talking about you, not about the government and I’m just saying again, you could say we’re going to allow free movement of people to continue after Brexit. You could say it now, it will be clear – why not?

JC: Diane Abbott has made it very clear our migration policy will be based on the needs and rights of people to work in this country just as much as British people who work overseas and we will guarantee all those rights of EU nationals that are currently here and their rights of permanent residence and of family reunion.

Me: Thanks, Jeremy – clear as mud.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

January 2019

Pre-vote summary: the DWA, the DPD and free movement

The crunch vote on the UK government’s Brexit deal was due on Tuesday evening, 15 January, in UK’s parliament. The deal, widely expected to be voted down, came in the form of two documents: the draft withdrawal agreement (DWA) and the draft political declaration (DPD) – both already agreed by the EU (see above).

What did those apparently doomed documents say about EU free movement of people (still the elephant in the room)?

May said the DWA ended free movement. It didn’t – not directly. It said from January 2021 the UK could set its own rules.

The DPD also didn’t say free movement would end. Rather, it implied free movement would have already been ended, saying:

‘Noting that the United Kingdom has decided that the principle of free movement of persons between the Union and the United Kingdom will no longer apply, the Parties should establish mobility arrangements…’

Fortunately, the government’s recent white paper on immigration explained their policy: free movement would end in 2021 after the implementation period.

Unfortunately, the white paper also proposed what could be called free movement 2.0: for at least four years after 2021, unlimited numbers of low-skilled migrants from Europe and elsewhere could come to the UK to fill vacancies in sectors such as construction and social care.

So, May’s deal would have allowed the UK to set its own rules from 2021 and so control immigration. May’s policy was to end free movement in 2021, but then to run free movement 2.0 until at least 2025.

Brexit and free movement: the east European elephant

Contents 🔼

January 2019

May lost Brexit deal vote – Corbyn lost no confidence vote

On 15 January UK premier Theresa May lost the crunch vote on her Brexit deal as expected. She lost by a record-breaking margin of 230 votes (432 to 202). After the vote, opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn tabled a motion of no confidence.